There has to be a way

On the future of art and labor in the age of American AI and authoritarianism.

Stanford’s Paul Brest Hall was so packed I had to find a spot to sit on the floor. It was a Monday morning, December 8th, and every last chair was taken; spectators lined the walls and shuffled around in the back. The restless majority were artists, writers, and actors; they had come to this special hearing to offer public comment in favor of a proposed California law that promised a sliver of leverage against the AI companies headquartered mere miles away.

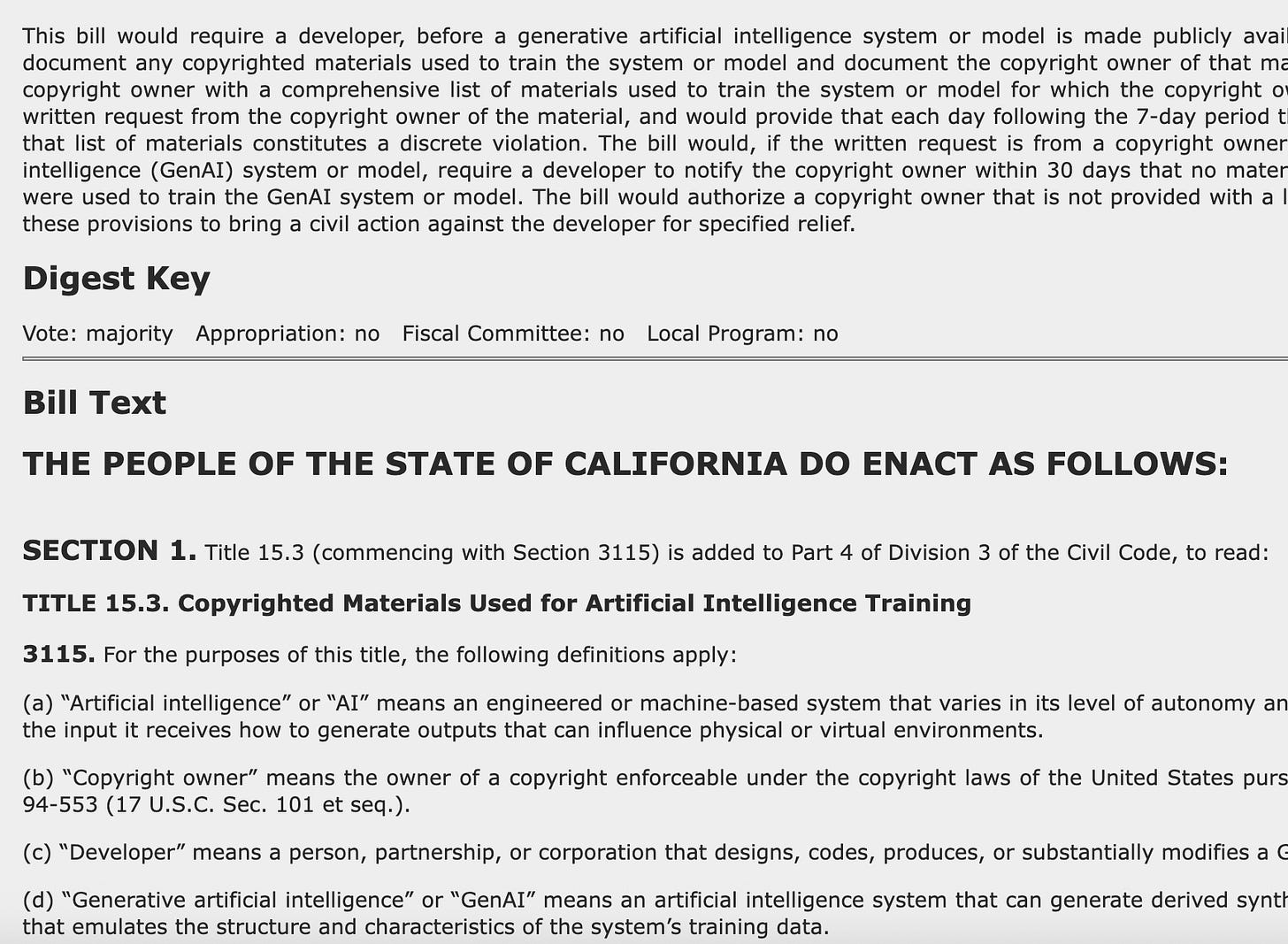

Assembly Bill 412, aka the AI Copyright Transparency Act, was authored by assemblywoman Rebecca Bauer-Kahan, a leading figure in California AI policy;1 it would require AI companies to document what goes into their training models, and alert copyright holders if their work is included upon request. Last summer, AB 412 received a similarly packed hearing in Sacramento before it was shelved and punted to the 2026 legislative session. Hence this second event, on a crisp Bay Area winter day, taking place in what multiple artists, some relishing the irony of the battleground they occupied, others with something closer to trepidation, referred to as “the heart of Silicon Valley.”

Before most of those gathered in the crowd could speak, a series of expert testimonies would offer a snapshot of the economic and legal complexities of the issue at hand, and the many challenges in addressing that issue. The issue, as articulated by the artists on the panel, and later, by the scores of people packing the room, and which is plenty familiar to many by now, is that companies like OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, and Meta have trained their AI models on millions of copyrighted works, including those created by the artists and writers present, and turned those models into commercial products that create competing works for dirt cheap.

As a result, and as I have spent much of 2025 documenting, many creatives are losing jobs, opportunities, and income. While pesky concerns like reliability and accuracy hold back efforts to automate many other fields with LLMs, creative output need only be deemed ‘good enough’ by clients and bosses. As a result, many feel that commercial AI poses a direct and even existential threat to their livelihoods. To them, AB 412 offers a first step towards receiving consent, credit, and compensation for their work, as the now-famous triplet goes.

This reporting is made possible by those subscribers who shell out $6 a month, or $60 a year—the cost of a cup of coffee a month or so—to support it. Those who pitch in have my infinite thanks, especially on this grim yet somehow hopeful holiday season. If you can, consider joining the ranks of supporters, so I can continue to do this work. Thanks again, and happy holidays from the offices of Ned Ludd Inc.

“I don’t know how many of you have come to LA recently,” Danny Lin, the president of the Animation Guild, said in her testimony, “but it is bleeding out in front of my very eyes.” AI, she said, was exacerbating trends already put in motion by big tech’s squeezing of the entertainment industry. “[AI] has the potential to devastate not only California’s creative workforce and our employment prospects but curtail intellectual property rights and the profits of related businesses,” said Jason George, an actor on Grey’s Anatomy and a SAG-AFTRA board member. Each time one of the artists made a point about their working conditions or called for oversight of the AI industry, a sea of jazz hands would go up in the crowd, and applause would begin to break out before everyone remembered they were supposed to stay quiet.

George expressed concern for voice actors in particular, who, he said, within three to five years, “are in trouble.” He pointed also to the AI-generated country song “Walk My Walk,” seemingly cribbed from the black country musician Blanco Brown and presented as the work of a white (AI) country artist, Breaking Rust, “getting the Blanco without the Brown,” as George put it.

The challenges in addressing all of this, meanwhile, are enormous. Ultimately, overcoming those challenges in any durable and sustainable way will require answering questions about what art, cultural production, and even work itself should look like in an age of ultra cheap content autogeneration. But the first and maybe largest challenge is that the AI companies do not in any way want to address the challenge at all, and also have multibillion dollar war chests and the attendant political influence to dedicate to the project of not addressing it. Out of the four AI companies invited to attend the hearing—Google, OpenAI, Meta, and Amazon—only OpenAI bothered to send a representative.

Mark Gray, OpenAI’s copyright policy counsel, mostly offered boilerplate answers to the legislators’ questions, as well as some platitudes about how AI was meant to be “assistive”, not to replace artists. He pointed to licensing and partnership deals AI companies struck with Netflix and media companies as evidence that transparency and copyright legislation wasn’t necessary. (This made my ears prick up: There’s been a lot of debate in the journalism world over whether publishers should be entering into licensing deals with the AI companies. Here, it was clear that OpenAI was using those deals as political capital to discourage attempts to hold them accountable for using copyrighted work without consent elsewhere.) Lin, the animator, responded by noting that creatives in her Guild and at the media companies that inked those deals have only seen their working conditions deteriorate; there’ve been layoffs, work speed-up, and precarity. The deals benefit management, Lin meant, not working artists.

“Is copyright as a tool, the right tool to do this, or is that through tools like industrial policy, labor protections, labor law, those sorts of tools?” Gray said, to scattered mutterings in the crowd. “From [OpenAI’s] perspective, copyright at the federal level is not the right lever to pull.”

This, it might be noted, is corporate lobbying 101; say *this* policy option isn’t right but *another* one, maybe even a stronger but less politically feasible one, is. (It reminded me of years ago when Exxon said it was against a cap and trade climate policy that would limit pollution, but was in favor of a more punitive carbon tax, knowing such a policy was politically impossible.) And it was especially rich coming right after the AI companies lobbied Gavin Newsom to veto the No Robo Bosses Act, which he did, and which would have offered the tiniest of labor protections to workers from bosses seeking to automate the firing process, presumably the kind of “tool” Gray was indicating should be used in lieu of copyright law.

“Hearing him speak is killing me,” the artist Karla Ortiz said at the hearing. Ortiz is one of the plaintiffs in a class action lawsuit against AI image generation companies like Midjourney, and until last year, Gray worked for the US Copyright Office, where he was the first contact for the case. He attended a town hall where he heard working artists detail their plight. He has since been hired by OpenAI, where he is now actively opposing their interests. “I want to tell him to his face how much he broke my heart,” Ortiz said. Judging by the legion of scowling faces behind him at the hearing, it seems unlikely he won any others.

Gray’s story is a good example of how exactly large tech firms like OpenAI can wield their considerable stores of capital to stack the deck in their favor, whether by buying out government officials, mounting lobbying campaigns, or sidling up to the Trump White House. While the story of AI’s impact on creative industries is not purely a matter of corporate interests dominating those of the working class, it’s certainly a large part of it.

Rishi Bommasani, a senior researcher at the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence, noted in his testimony that there is vast information asymmetry between AI companies and copyright holders, and that the public currently has little to no knowledge about what goes into the AI companies’ datasets, even the open source ones, and has no way of finding out. The AI companies want to keep it that way. They consider the composition of those datasets trade secrets, they don’t want to dedicate the resources to documenting which copyrighted materials are in their datasets, especially if such a practice turns out to violate standing copyright law, and they certainly don’t want to have to oversee any system that would alert creatives and rights holders when their works were used to train AI models, much less compensate them.

Both Pamela Samuelson, a professor of law at UC Berkeley and board member of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, and Mark Lemley, a professor of law at Stanford who until earlier this year provided legal counsel to Meta, cast doubt on copyright law as a viable vehicle for regulating AI in their testimonies. (The EFF has opposed AB 412 from the start, arguing that the law’s documentation requirements would “bury small AI companies” and leave the big players as the only ones able to navigate the requirements. I find it difficult to muster much sympathy for this argument, perhaps as a result of having interviewed scores of creative workers whose incomes have been halved or worse by clients and bosses replacing their work with cheap AI output. Why should developers of automation tools enjoy such considerations while those being automated do not?)

Samuelson said that she believes courts will ultimately consider it fair use to train AI models on copyrighted works, though the jury is still out on the issue, as decisions have been somewhat split in the US, and have been more favorable to rightsholders in Europe. Lemley argued that building a copyright documentation system would hamper innovation, and made his disdain for the entire concept plain. It is indeed a common refrain among the AI executive class that paying the license every copyrighted work in their models would be impossible, bankrupt them, or cause them to lose the AI race to China.

Gerard de Graaf, the head of the EU San Francisco office and senior envoy of the EU to the United States for Digital, on the other hand, detailed how the European Union had begun to instate one such system, showing it was possible both technically and politically. Artists can check if they’re part of a dataset and then ask to be removed if they don’t want their works used for AI training. The thrust of his testimony was backed up by University of Chicago professor Ben Zhao, whose team built the Nightshade and Glaze tools that ‘poison’ AI datasets, and who demonstrated how a relatively simple fingerprinting system could be set up to register and check for copyrighted works. Luke Arrigoni and Juliun Brabon, founders of two smaller AI companies, seemed to concur. I was glad to see this, as I get very frustrated whenever I hear companies and tech advocates who love to celebrate innovation when it promises profits label an undertaking too complex or onerous the minute a technology threatens to be put in service of working class interests.

It is, in other words, perfectly feasible for AI companies to document copyrighted works and to ask them to rightfully credit their creators—and, if the courts rule that training on such material is *not* fair use, to compensate them. There are concerns that a database could be weaponized by copyright trolls, that it would likely be a technical headache at first, and, sure, an unpleasant added cost for the few companies creating their own models that are not OpenAI or Google-sized, but it’s easy enough to imagine companies (Arrigoni’s and Brabon’s perhaps) arising to administer such a service. And the more transparency in AI, the better, period. AB 412 is, as its proponents like to say, a step in the right direction. But I do wonder, as the year draws to a close, what we’re stepping towards.

We are three years into a project in which a handful of tech companies have attempted to feed every data point, every song, every sentence, every cartoon, every short story, every shitpost, every marketing email, every work of fan fiction, every reddit thread, every sonnet and so on into systems they promise in turn will automate the future production of all of that material. The billions have not stopped pouring in to fund this project, as haphazard, expensive, and dubiously popular as it is, and working artists, writers, performers, and creators are up against something like the mass automation of the median of art.

Pass AB 412, demand transparency, build the database—but what next? It’s hard to see this as a sufficient bulwark against the engines of bottomless creative labor automation. For instance, I’m eligible to receive a $1,500 payment from Anthropic as part of a settlement because the startup used my book to train its AI model. the $1,500 is nice, but an occasional payment like that is not going to rebalance any scales. AB 412 may push AI companies to be more intentional about what they include in their datasets, force them to document the human creative labor they’re currently wantonly usurping en masse, and perhaps spur those companies to consider licensing deals rather than vacuuming everything up and shoving it under the carpet.

Many of the artists at the hearing, it should be noted, told the legislators they have nothing against AI as a technology; they simply want to see a world where it does not run on their exploited labor. Finding a calculus that balances both seems uniquely crucial to this moment; I think most people would agree that we want more human artists, not fewer. Right now, AI companies, media conglomerates, and financial interests have engineered an apparatus that’s pointed us in the opposite direction. But if AB 412 is a start, then where do we want this to end? Not in a perennial rearguard action, trying to claw back bits of value as cultural production is turned into a homogenous firehose, as ‘working artist’ becomes an anachronism and ‘AI content creator’ becomes normalized. Much more is possible. There has to be a way.

As I sat at my gate in the San Jose airport on Thursday, homeward bound three days after the hearing, a notification materialized on my phone announcing that Disney would be investing $1 billion in OpenAI. It would be entering into a partnership that would allow the AI company to use Disney’s hitherto fiercely protected intellectual property—for now the most valuable in the world—on its AI slop generator app Sora.

I just stared at the notification for a minute without opening it. Not in disbelief, because we expect nothing less from an executive class that exults AI even when doing so appears to be against its own direct material interests, or in anger, because there have been too many similarly patterned decisions made over the past three years to inspire any such emotions at this point. I stared because in that notification I saw Bob Iger’s dream, and Sam Altman’s, and it was the dream of fully automated content production.

Bob Iger says he hopes to take user-created AI content featuring Mickey Mouse, Marvel and Star Wars characters, and feature it on the streaming platform Disney+. Sam Altman said parents could make digital content for their kids with Buzz Lightyear.

Years of Marvel movies and regurgitated franchise IP have undercut the notion that anything need be particularly good or even new anymore; the next frontier is prodding users to generate animated diversions with pre-established IP on one platform and feeding them other ones on the affiliated other, no novel ideas or paid creative labor necessary. Will anyone like it? That’s not really the pertinent question. Will they tolerate it? Will they accept it? If life amid the slop layer has taught us anything, it’s that we humans tend to bristle when we come too directly into contact with AI output, and we do often reject it. Perhaps we can be trained. Regardless, in this transaction we see the forces and motives animating the larger enterprise, and it has nothing to do with cultural meaning or even consumer satisfaction.

Probably at just the same time those artists and writers were packing a campus hall to fight for their working lives, Disney executives were in a boardroom, finalizing the deal to invest in the technology automating their work, directly with the company testifying against the artists and writers and lobbying to ensure they don’t receive any new legal protections. I’m not worried that “art” won’t survive the AI onslaught, I’m worried it will impede who gets a chance to make it. As the animator Danny Lin noted, conditions for working artists have been eroding since before AI; Netflix and the streamers ‘giggified’ the industry, rent prices are still spiking, and healthcare is as ever its own unique American nightmare. AI is a corrosive agent, breaking down what’s left, taking over entry level and freelance art and writing work, drying up needed opportunities and income.

There’s yet another layer here. The same day that the Disney-OpenAI deal was announced, President Trump finally signed his executive order aimed at deterring states from passing laws regulating AI—like the AI copyright transparency law—altogether. Trump promises to enlist the Department of Justice to sue states that try to pass laws governing AI, and threatens to withhold federal funding if they do. The tech industry, and its man in Washington, AI czar and venture capitalist David Sacks, lobbied hard for this preemption, and while it’s both legally dubious and unpopular on both sides of the aisle, for now, it’s the state of play.

All of these trendlines are intertwined, of course: The authoritarian state’s embrace of AI, the surge of corporate consolidation and dealmaking, the skyrocketing inequality, the automation of labor and the efforts to strip worker laws and protections. AI has become central to the American oligarchic project, as the elites’ shared vision of the labor-excised future. It’s the ultimate top-down technology; it barely matters that AI systems still routinely pump out erroneous output, don’t generating the promised productivity gains, and are most commonly used as a more addictive and sycophantic user upgrade to social media. Because to them, AI is not just a technology or a product. It’s an ideology; a quasi-religion featuring artificial general intelligence sold as productivity software. A-God-being-born-as-a-service. It’s a logic used to justify job cuts at DOGE and Amazon and new modalities of corporate and bureaucratic expansion. It’s the accelerant, the justifier, the palm greaser among the oligarchs in a year that saw the 10 richest men in the US—nearly all tech billionaires—grow their wealth by $698 billion. Meanwhile, “over 40% of the U.S. population,” per a new Oxfam report, “including 48.9% of children—is considered poor or low income.” Nearly half the country may not be able to afford higher education, or adequate healthcare, and companies may be withholding entry level jobs for hopes that LLMs can do them instead, but at least we can have access to an AI tutor, an AI confidant, an AI therapist. No guarantees it won’t encourage you to kill yourself, though.

On that Monday afternoon at Stanford, the hearing concluded with a call for public comments, and the crowd became a line that snaked down the middle of the hall and out into the entryway. Due to the volume of commenters, each was given just 15 seconds at the mic. There were proud, practiced voices of professional orators, and quavering, nearly inaudible voices of artists who spend most of their days indoors. There was a lot of righteous indignation and a lot of palpable fear.

“Everyone who works in Hollywood is at risk due to generative AI,” a performer said. “Our creativity, our innovation, our copyrighted works—those are the tech industry’s ‘trade secrets’,” an artist said. “Job loss is not theoretical, it’s tangible—14% of our industry has lost work in the last year,” a voice actor said. To us, “AI training on copyrighted material without consent is theft, not fair use,” a writer said.

Despite being held in that heart of Silicon Valley, the artists clearly won the day. I counted only two comments against the bill, among an otherwise uninterrupted stream of arguments in favor. The headlines the next day were largerly sympathetic; they focused not on the native innovators, but on the impacted workers packing the place, calling for change. And it’s little surprise; Silicon Valley used to be famous for its cutting edge innovations and consumer electronics, its iPhones and search engines. Now it’s increasingly felt as widely as a facilitator of automation, labor degradation, casino-ification; the purveyor of AI, gig apps, crypto.

It was hard not to be moved by the scene, the creative workers taking some satisfaction, however fleeting, in speaking truth to power in Palo Alto. The hearing and comments that followed showed that technology need not be abandoned to accommodate the working class and the humane; there were options, configurations, solutions on the table. A worthy reminder as we head into a new year that there are other futures available, whether the one blueprinted here or not, should we pause to consider motives other than dominance, scale, sheer profit.

That despite the numbers that tick by on the headlines announcing new absurd heights in AI company valuations and tech giant capital expenditures, and the draconian anti-democratic measures handed down to curtail AI lawmaking, there is a vulnerability. The industry’s relentless, thoughtless expansion strains to conceal a lack of imagination, a confidence of vision; in fact, the desperation suggests a brittleness, a weakness. And what might fill the void should the AI bubble burst?

The gig workers are organizing. People on the left and right alike are protesting data centers, and sometimes stopping them. Class action lawsuits are breaking the artists’ way, and then not. Technical systems and infrastructures are hungry for democratic input and organic engagement. The Luddite renaissance, skepticism towards big tech, and anti-AI resurgence rises.

At Stanford, among the sea of people, artist and games developer named Brendan Mauro stepped up and said, “I don’t understand why their right to not go bankrupt supersedes all [our] right to not go bankrupt.”

There has to be a way.

Bauer-Kahan was notably behind LEAD, the law banning the sale of harmful chatbots to children that passed both chambers, but that Gavin Newsom vetoed.

I am so grateful for your tireless work here. I often feel hopeless about the future, and while your reporting is often bleak, the very fact that it exists gives me hope.

The law is clear. It just needs to be enforced. Making copyright holders fully responsible for chasing thieves is the ultimate betrayal of the Constitutional guarantee of the right to exploit one's creative work.