What Trump really wants with AI

Trump's AI agenda is often described as a push for deregulation; an effort to cut red tape so AI companies can innovate. In truth, it's a big government project with designs toward domination.

As Donald Trump issued his latest round of threats to seize Greenland, he illustrated his intent with, what else, some AI slop.

Trump posted the above image on Truth Social, along with another one depicting some kind of a strategy meeting in the Oval Office being held in front of a map with the United States, Greenland, and Canada all colored in like the American flag.

This sort of thing has become standard practice for Trump and his team. The administration shares AI-generated images on social media so frequently it’s been termed slopaganda. It tracks: Given that it’s voluminous and cheap, fundamentally unconcerned with conveying truth or accuracy, free of nuance, and generally adheres to a gaudy, homogenous aesthetic, it’s fitting that AI imagery has become an ideal vessel for state expression.

But the embrace goes beyond aesthetics. The administration’s AI images, from the ‘Ghiblified’ picture of a woman crying as she’s arrested by ICE, to grainy faux video clips of Obama getting arrested, to that reel of a razed and redeveloped Gaza, to the more recent ‘Defend the Homeland’ and Greenland conquest posts, are unified by the same impulse: to project MAGA dominance.

In the administration’s repeated use of gen AI, Trump’s not just articulating his policy aims with AI, but articulating his approach to AI policy, too. Both are rooted in the drive to dominate. It’s a point I think we’d do well to underline as we enter year two of the Trump administration and year four of the AI boom, and as Trumpworld and Silicon Valley bind their projects, personnel, and futures ever closer together.

Take what was perhaps the AI industry and the Trump administration’s key shared ambition last year: A 10-year moratorium on state AI laws, colloquially known as preemption. At the behest of Meta, Google, OpenAI, and other tech firms, as well as crypto and AI czar David Sacks, Trump allies tried to get legislation to that effect passed in Congress twice. It came up short both times, facing intra-GOP opposition as well as general blowback on the grounds that it was an optically toxic gift to big tech and fundamentally antidemocratic. It was instead, as readers of BITM know, turned into an executive order that aims to accomplish the same ends, just via coercion, withholding state funds, and threat of litigation from the Justice Department.

Now, the reason that both tech CEOs and Trump officials say they need preemption is to ensure American AI firms can innovate freely and rapidly, aren’t bound up in red tape, and thus can “beat” China in the AI race. You may have heard the line about how no one wants 50 different rules from 50 different states. As a result, Trump’s AI policy is often framed as a deregulatory agenda; an effort to unfetter enterprise from rules and roadblocks for the benefit of business, or even, more critically, for the benefit of his newfangled allies in the elite tech set. And while that transactionalism is certainly a part of what’s happening here, that’s clearly not the limit to Trump’s ambitions with AI.

Two recent policy papers, “The mirage of AI deregulation,” by Alondra Nelson in Science and “The Big AI State,” by Brian J. Chen in Data & Society, each argue that Trump’s federal engagement with AI should be understood not as orchestrated in the interest of fostering a free market, but as a big government project to concentrate state power. Trump’s agenda is not a push for “deregulation” as much as it is, like the Greenland threats he uses AI to illustrate, a deliberate quest for domination.

I’m still trying out running some ads here to help support the editorial operation, some 98% of which is supported by paid subscribers. (If you find value in this work, and you’re able, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. I lost about 20 paid subscribers after my critical examination of ICE, X, and the mechanics of socially mediated American authoritarianism, and if that post was why, well, good riddance. But to be frank, it does me nervous going forward, and your support means more now than ever.)

So! Today’s edition of BITM is sponsored by DeleteMe, whose mission is to hunt down and, yes, delete the information that data brokers have hoovered up about you over the years and made publicly accessible with or without your consent. DeleteMe is Wirecutter’s top-rated data removal service, and I’ve used it myself to locate and eradicate 100 or so sites that were listing and selling personal info like my home address and phone number. If you’re interested in trying out DeleteMe, sign up here and use the code LUDDITES for 20% off an annual subscription. Thanks all, and onwards.

Alondra Nelson, a former director of science and technology policy in the Biden administration, and who was more recently tapped to serve on Zohran Mamdani’s Transition Committee on Technology, argues that rather than deregulating the AI industry, Trump is merely moving the regulatory apparatus upstream, under his control:

Framed as relief from regulatory burden, preemption represents an aggressive assertion of federal authority that forecloses democratic experimentation at the state level. Whatever one’s view of state-level AI policy, federal preemption is itself a form of regulation—one that concentrates power while insulating it from local accountability.

The Trump administration is not removing government from AI regulation; it is concentrating governmental power at the federal level while deploying it through mechanisms—investment, ownership, research funding, immigration controls, and preemption—not typically classified as “regulation.”

(Emphasis mine.)

Nelson argues—correctly, I think—that Trump is doing far more than merely helping Silicon Valley cut red tape and far, far more than taking “a hands off” approach to federal AI policy. Given the headlines and commentary around the AI moratorium in mainstream and tech-friendly spaces, you’d be forgiven for thinking Trump’s AI policy has been orchestrated in the interest of nurturing free enterprise. It’s closer to the opposite. Trump is in fact overseeing an enormous state project, directly and indirectly shepherding national resources towards an industry that’s in turn led by a handful of tech giants.

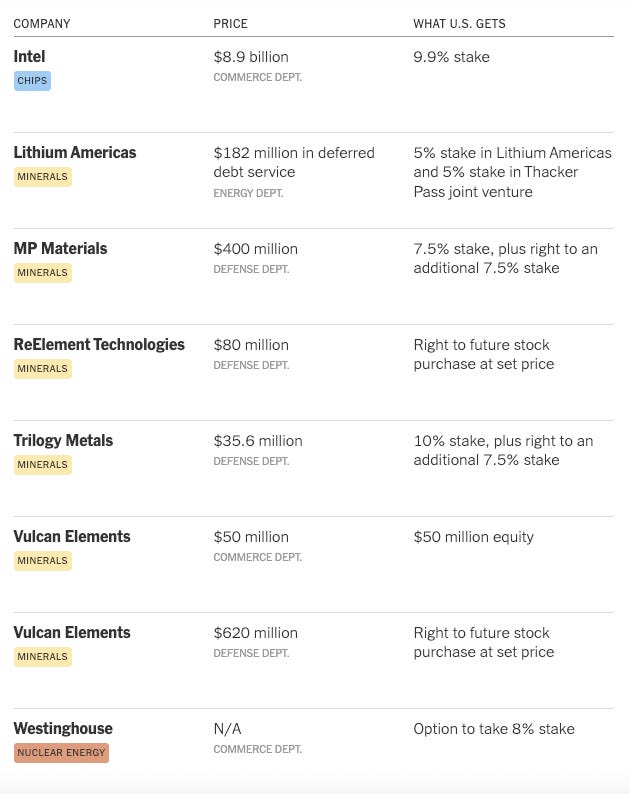

Most obviously, there are the direct investments. Under Trump, the federal government took a 10% stake in Intel for nearly $9 billion, partially nationalizing one of the nation’s legacy tech companies. What’s made fewer headlines is that the Trump administration has also taken a stake in eight other private companies, collectively worth hundreds of millions of dollars, crucial the tech industry’s supply chain. The New York Times published a rundown of the investments in November:

It’s also very much worth noting here that Trump cut a deal with Nvidia to allow it to sell previously off-limits high-tech chips to China, in exchange for 25% of the revenue. That’s a huge federal finger now firmly on the scale of the operations of the single most valuable company—at time of writing it’s worth $4.5 trillion—on the planet, and the one most central to the AI boom.

Nelson also argues that by restricting immigration, especially through the H-1B visa program, slashing national research funding for some subject areas (environmental impacts, algorithmic bias and labor impacts, for instance) but not for others, and engaging in projects like preemption with the heads of major AI firms, Trump is in fact very much regulating AI. He’s just doing it with the aim of expanding federal power—over a technology and industry increasingly dependent on his largesse—not protecting the public interest.

Brian J. Chen’s brief, The Big AI State, drills even further into the details of Trump’s statist AI project:

To secure US dominance of AI, the federal government is organizing the AI industry in three ways: it is (1) derisking domestic infrastructure investments, including by land use deregulation and favorable financing arrangements, while (2) leveraging commercial diplomacy to open new markets for foreign data centers, and (3) making equity investments to ensure sufficient demand and solvency throughout the supply chain.

Chen focuses first on the government’s role in enabling and encouraging the data center buildout, by offering tech firms favorable land use policies like leases on public land, expedited and circumvented environmental review, and even, soon, potentially, outright financial assistance. The Biden administration issued an executive order opening federal lands to data center development, and the Trump administration has put the pedal down and “opened up its inventory of publicly-owned lands to private project developers.” It has, Chen notes, “ordered relevant agencies to identify and lease federal lands for data center projects, coal infrastructure, and nuclear power plants.”

Trump has issued no fewer than three executive orders—for data center, coal, and nuclear power expansion—encouraging the use of categorical exemptions to bypass otherwise legally required environmental reviews. The EO on data center orders the Commerce Department “to provide financial support for qualifying projects (data centers and supporting infrastructure). Such support includes ‘loans and loan guarantees, grants, tax incentives, and offtake agreements.’”

Chen also notes that Trump is proactively working to open and secure new markets for American AI companies; he cites the “Promoting the export of the American technology stack” executive order and points to the Stargate UAE project, a billion dollar data center to be built in Abu Dhabi, as an example. It’s notable that Trump’s EO incentivizes the exporting of the full AI stack—as in, software, hardware, and infrastructure; its primary intent is getting more data centers built abroad running American AI systems. Finally, Chen’s brief overlaps with Nelson’s in detailing the state-led investment in AI, energy, and mineral extraction firms important to the industry’s supply chain.

Both Nelson and Chen’s pieces are very much worth reading in full, and together they paint a compelling portrait of how the federal government under Trump is working to grow its power with AI. Through this lens, it becomes all the clearer why OpenAI almost casually started making noise about wanting a federal “backstop” for chip and data center investments; AI executives had likely simply gotten so used to discussing such ideas in private with the administration, to where it had become so normalized that CTO Sarah Friar felt comfortable speaking it aloud, in public, to an audience that was still under the impression American AI’s fate was dictated solely by free market capitalism. It should also provide food for thought about what might happen in the event of the AI bubble bursting, or in the event of a downturn; what happens if investors back out of sustaining OpenAI’s immense cash burn, and it can’t IPO in time? Given the current interests and configuration of the state, a semi-nationalized OpenAI is entirely thinkable.

Less examined in both briefs, necessarily, is the why behind all this. Why is the Trump administration so vested in underwriting a nationalist-leaning big government AI project, and what’s the ultimate aim? I’ll take a stab at that here.

The most obvious, and over-simple reason is the one explored in these pages many times before; Trump’s inner circle is larded up with Silicon Valley influence, initially as a result of the openly right wing of the industry buying their way in, as with David Sacks, or expending their political capital on the president’s behalf, as with Peter Thiel, or both, as with Elon Musk. But this infusion of the tech elite into MAGA politics has been far from seamless, with plenty of longtime supporters, like Steve Bannon and Laura Loomer, openly chafing at and challenging the Valley’s rise in the party. Trump and his inner circle have made at least a back of the napkin calculation that given tech’s money, infrastructural advantages of currying their favor, and the larger AI project more broadly, will be worth the internal backlash.

The Trump administration saw opportunity to transform AI into a political project early on; this is why JD Vance’s first speech in Europe as vice president was spent announcing America’s intent to dominate with AI, and that the rest of the world was free to fall in line. That speech presaged much of what was to come with the administration’s approach to AI, both regarding its policy and use.

The ‘bigger is better’ ethos that undergirds the hyperscalers’ project is certainly appealing to the Trump team, and easily grokked by it; according to the current rules of engagement, whoever gets the most investment, most data centers, and the most energy, wins. That’s certainly an appealing formula to Trump, who is of course obsessed with “winning” but moreso because obtaining the access to energy and infrastructure necessary to “win” puts the world’s richest men and largest companies at his mercy. Here’s a technology that everyone is saying is the future, promises a capacity for mass job automation, surveillance, and control and that requires a massive amount of coordination from the state to execute. It thus offers the federal executive a huge amount of leverage over anyone who wishes to build that technology.

(There are certainly multiple factors that explain the executive tech set turning almost immediately into full time Trump supplicants, including natural “anti-woke” tendencies and frustrations with workplace protest or whatever, but an underexplored element is perhaps the extent to which they recognized that competing in the LLM race would require an unprecedented amount of buy-in from the state, and particularly a state run by an aggressively transactional president.)

To that end, the same goes for securing foreign partners for US AI firms; building out data centers on foreign soil with servers and software owned and operated by American technology companies—that, by the way, are increasingly coordinating directly with the federal government and Trump himself—is a new kind of imperial project. Google, OpenAI, and the like are canvassing foreign markets, offering cloud services for cheap, and trying to get companies and officials to buy into (and get locked into) their tech ecosystems; under Trump, those efforts are now incentivized and in some cases arbitrated by the US government.

In sum, the Trump administration is regulating the AI industry to achieve both a specific vision of imperial and expansionist American power, and to suit its executive’s own whims as a gangster capitalist. And I do think some of this reflects down to Trump’s own affinity for AI, on a user level. While most of the policy is surely hashed out by Sacks, industry groups, officials like Michael Kratsios, (Nelson’s successor as the director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy), and, yes, perhaps ChatGPT itself, Trump clearly approves of generative AI. Much like Trump was skeptical of crypto until he got his hands on it and realized it was a world-historic opportunity to openly and lazily facilitate grift, the slop issuing from his personal feed on Truth Social and on official administration accounts reveals a affinity for the technology.

With generative AI, Trump gets to see his trollish fantasies instantly made, if not flesh, then at least visceral. That large swaths of liberals are doubly offended by his AI posts—both by the content itself, and by the medium used to create it—probably only sweetens the deal.

It’s not hard to imagine the satisfaction Trump derives from seeing big, tacky-looking depictions of his enemies getting crushed, his conquests dramatized, the future rendered in his image. And that, ultimately, is what Trump wants from AI.

For further reading on the subject of AI as the aesthetics of fascism, read Gareth Watkins.

Here’s a bonus quote from the Nelson piece that’s worth considering, and is true not just with regard to AI but the myriad technological systems that shape our lives:

“When decisions about the technologies that will shape our work, our health, our capacity to know and to communicate are made without public justification, outside ordinary channels of accountability, we are not governing ourselves. We too are being governed. The mirage of AI deregulation obscures this truth. Power has not retreated. It has moved—and democratic accountability requires following it there.”

Bonus bonus:

I was experimenting with ChatGPT to see how long it might have taken Trump to create a Greenland conquest photo that served his purposes, and I was struck by how bad the images are. This is a technology that I keep getting told has made unbelievable progress over the last year, and while this would probably suffice in a pinch and could be fixed with a few more edits, the prompt “generate an image of the trump administration planning to annex Greenland” depicts former national security advisor (and now Trump critic) John Bolton and former vice president Mike Pence as parts of his cabinet.

The next one was worse—it was supposed to show Trump annexing Greenland to the US, and well, you can see the issue here:

Bow down before the inevitable AGI, I guess.

Okay, onto some links and shouts:

-“As new technologies (not immigrants) replace human labor, “machine breaking” as a tactic of rebellion is taking on a renewed vitality.”

Read the great labor reporter Sarah Jaffe’s latest feature, “Capitalism Without Humans” in In These Times. BITM and the work of many other good Luddites is sourced throughout, and it’s a great read.

-Carleton University teaching assistants are fighting for common sense AI guardrails, but management won’t meet them at the table.

Sign their open letter and shout your support here.

-Cal State University is considering laying off instructors while investing in OpenAI. There’s petition going for that too:

-“Trump administration concedes DOGE team may have misused Social Security data” by Kyle Cheney for Politico:

From the ‘who could have seen this coming’ dept:

Two members of Elon Musk’s DOGE team working at the Social Security Administration were secretly in touch with an advocacy group seeking to “overturn election results in certain states,” and one signed an agreement that may have involved using Social Security data to match state voter rolls, the Justice Department revealed in newly disclosed court papers.

On opting out of the Anthropic settlement:

The author Daniel Howard James has a piece considering the recent Anthropic class action lawsuit and settlement that’s worth a read.

For what it’s worth, I just opted out of the settlement myself. I think it doesn’t do enough to hold Anthropic and AI companies accountable, it doesn’t move the needle in an actionable way on the policy front, and frankly, the sum it promises to deliver to authors is too small. There are other, stronger lawsuits afoot that I’ll dig into in a future post.

Okay okay, that’s it for today. Until next time, stay warm out there, and keep those hammers up.

Possibly before you wrote this, Carney spoke at Davos about "middle countries" creating alliances where their goals were in common. Europe is looking to exclude and/or regulate US technology. China blocked imports of NVIDIA H200 GPUs, possibly to remove supplier leverage and/or to spy on China. The world is intent on forcing the USA to stay in its nattowed "hemisphere," which will reduce the power of US technology in the world. The hegemon will cripple itself.

Stupid is, as stupid does.

I've been reading Palo Alto by Malcolm Harris.

What is old is new again in the synergy of California Tech and American dominance