AI profiteering is now indistinguishable from trolling

And what that says about the state of the AI bubble

In late 2024, billboards and bus stop posters bearing the slogan STOP HIRING HUMANS started showing up in San Francisco and New York. The ad spots, which turned out to be the handiwork of the enterprise AI company Artisan, went viral, buffeted by an outpouring of rage on social media. The company said it was just trolling. “It’s really just a viral marketing tactic,” the 23 year-old CEO Jaspar Carmichael-Jack wrote on a reddit AMA, “we don’t actually want anyone to stop hiring humans.”1 A few months later, the company closed a $25 million Series A funding round.

The company doesn’t train its own models or even build its own technology, it seems—it packages other LLMs into a software-as-a-service platform that aims to automate sales work—but whoever was behind that marketing campaign understood something about the AI boom early on: It’s all about the story. When you have a market as impossibly frothy as AI, it doesn’t matter if you have an AI-powered SaaS business with a decent UI. So does everyone else. If you want investors and the press to take note, you have to manufacture yourself a narrative, and one of the easiest ways to do so is, naturally, to troll.

A quick note before we power on: Thanks to everyone who reads, subscribes to, and supports this work. Blood in the Machine is made possible 100% by paying subscribers. If you value this reporting and writing, and you’re able, please consider helping me keep the lights on for about the cost of a beer or coffee a month, or $60 a year. And a big blast of sincere gratitude to all those who already chip in; you’re the best. OK OK. Onwards, and hammers up.

I’ve been thinking of Artisan a lot lately, as we marinate in what sure feels like the peak bubble days of generative AI. Of course, who knows, we’re in uncharted waters now, AI has eaten the American economy and the Trump administration wants to do all it can to keep the juiced times rolling, so we may yet linger in these heights of AI-inflated absurdity for a while.

But suffice to say we’re in a moment where $12 billion companies are formed entirely on the basis of one of the founders having formerly worked at OpenAI and literally nothing else. I am talking of course about former OpenAI CTO (and very very briefly tenured CEO) Mira Murati, who left OpenAI in September 2024. She announced her new company Thinking Machines the next February, and began seeking investors. Not only was there no product to speak of, she apparently would not even discuss her plans to make one with potential backers.

“It was the most absurd pitch meeting,” one investor who met with Murati said, according to the Information. “She was like, ‘So we’re doing an AI company with the best AI people, but we can’t answer any questions.’”

No matter, investors soon handed her $2 billion anyway. What’s more, according to WIRED, that amount made it the largest seed funding round in history. (Thinking Machines’ product has been announced now. It’s called Tinker, and I kid you not, it’s an AI model that automates the creation of more AI models. A little on the nose if you ask me!)

This, however, still pales in comparison to her former c-suite compatriot at OpenAI, Ilya Sutskever, who has raised $3 billion for his own product-less startup with a valuation at $32 billion, and whose chief innovation so far appears to be naming it Super Safe Intelligence, perhaps in an attempt to clear up any questions raised by the company t-shirt.

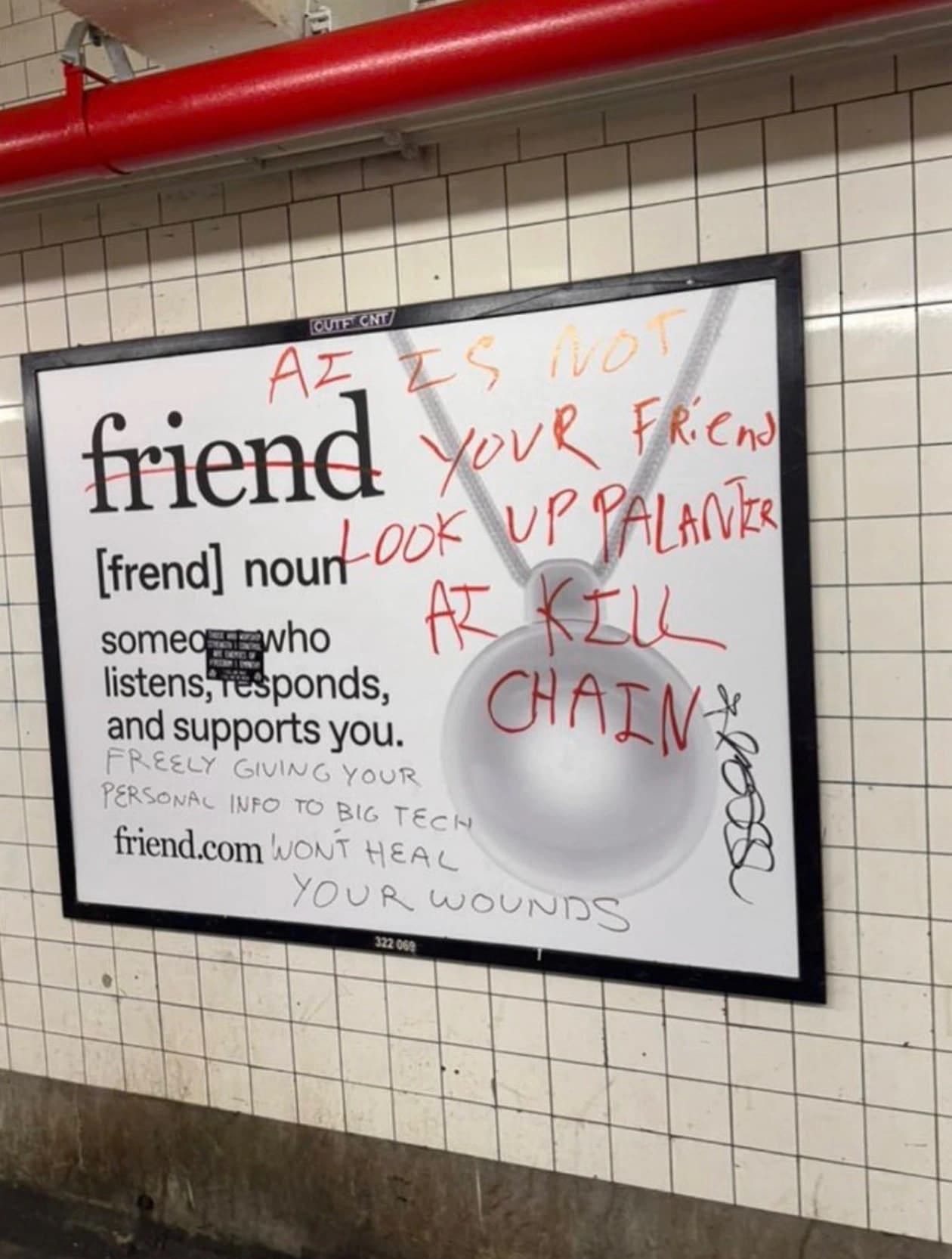

What really got me thinking about Artisan, however, were two stories I’ve been following in recent weeks: The first is about the New York City ad campaign from the AI startup Friend, which sells a little pendant device a user is supposed to wear around their neck and talk to and attract the ire of passersby with. The company plastered the NYC subway system with ads last month, and those ads were rapidly and thoroughly vandalized in what can only be read as an outpouring of rage at not just the Friend product, which they correctly identified as a malign portable surveillance device, but at commercial AI in general.

Here are a few more: Someone’s been cataloguing the beautiful carnage in this database you can peruse, too. (“Don’t be a phoney, be a Luddite,” one reads. You love to see it.)

The CEO of Friend, 22 year-old Avi Schiffman, claimed, perhaps dubiously, that this was the point all along. “I know people in New York hate AI, and things like AI companionship and wearables, probably more than anywhere else in the country,” he told Adweek. “So I bought more ads than anyone has ever done with a lot of white space so that they would socially comment on the topic.”

Why, exactly, did he do this? “Nothing is sacred anymore, and everything is ironic,” as he told the Atlantic. AKA “idk I’m trolling but it’s working because you’re writing about me.” Now, Friend is unique among AI companies in that other AI industry folks even seem to think Schiffman and his startup are a bad joke. But there are more ambitious practitioners afoot, too.

In Fortune, Sharon Goldman profiled the 23-year-old Leopold Aschenbrenner, who has one of the most man-of-his-times AI resumes I’ve ever seen. His first job out of college was at FTX, where he landed a gig through connections in the effective altruism movement, and worked until the crypto exchange collapsed because its CEO Sam Bankman-Fried was perpetrating large-scale fraud. Aschenbrenner then went to OpenAI where he absorbed the zeitgeist, was apparently arrogant and disliked before he leaked insider information to competitors and perhaps to the press, and got himself fired. He then self-published an overwrought document titled “Situational Awareness: The Decade Ahead,” which aped ideas from the AI safety and doomer communities and presented them as a scientifically-flavored report on how and when AI was going to become “the most powerful weapon mankind has ever built.” The document went viral, and then investors gave him $1.5 billion to manage a hedge fund. “Just four years after graduating from Columbia,” Goldman writes, “Aschenbrenner is holding private discussions with tech CEOs, investors, and policymakers who treat him as a kind of prophet of the AI age.”

Just so we’re clear about this: A recent college graduate whose only work experience was a stint at an infamously fraudulent crypto exchange and a job at OpenAI from which he was fired for leaking confidential information for personal gain, has maneuvered his way into managing $1.5 billion because he published a manifesto about end times AI and declared himself as a great knower of how this speculative scenario will play out. I do not know Aschenbrenner, I have never interviewed him, but if it turned out he didn’t believe a single word of that manifesto, I would not be surprised in the slightest. People who sincerely believe an apocalypse is coming do not tend to start hedge funds. Of course, Aschenbrenner may be a true believer in AI—as-Skynet, he may be a talented grifter who is skillfully exploiting those who lap up his pseudoscientific forecasting, or he may simply be trolling everyone into oblivion.

What matters is it doesn’t really matter. Trolling is now all but indistinguishable from AI profiteering. It may be one and the same. One way to look at the entire AI doom phenomenon, especially among the many executives and leaders in Silicon Valley who do not fully believe it but find it useful, is as an elaborate bit of trolling to get consumers and enterprise clients to buy their products. “This technology could kill us all, but use it to automate your email job while you can.”

There was, after all, a time in which, if a founder walked into a VC’s office on Sand Hill Road with a pitch for a big new company, and then the VC asked “what is your company going to do?” and the founder said “I can’t answer any questions about my company actually,” it would be clear the person was either delusional, or was trolling, and they would be shown the door. During a particularly absurd bubble around a technology with uniquely science fictional aspirations, however, investors might say, great, here is $2 billion.

Relatedly, being willing to eat shit for your AI startup that everyone hates may be seen by investors as a sort of perverse vouching for a future that so many others have deep doubts about.

All of these stories are absurd in their own ways, but they’re also telling us something about how the AI bubble is functioning. There’s been a relentless stream of talk about that bubble of late, and new investigations into the financial and economic indicators are published every day. (In fact, I’m working on my own contribution, a piece for WIRED, examining the role that narratives play in bubble formation.) As I’ll write more about soon, the *story* of AI’s innovation is different than that of the technology that has fed economic bubbles in the past. It promises investors a product with nearly limitless power, to automate all jobs or discover new medicines to patent and so on—the tech product to end all tech products, essentially—and lots of investors simply still don’t know how seriously to take it.

The sheer rate and ease by which unexperienced and smarmy guys in their early twenties are raising millions and now into the billions of dollars, largely by being willing to aggressively announce themselves as scapegoats for the future, or by publishing long blogs retreading tales of the terrible power of AI, should be yet another in an increasingly long line of AI-generated red flags. The signature moment in the entire AI boom thus far, to me, took place in the early days of OpenAI, when Sam Altman was asked about how AI products would make money. He told a crowd of industry folks, with a straight face, the plan was simply to build AGI and then ask it. So what if it’s just trolling, all the way down?

BONUS 1: The Luddites in CNN

I spoke with CNN’s Allison Morrow; who is, in my estimation, one of the very best business writers on the AI beat in the American mainstream press; about the recent rise of luddite activity. It’s a fun piece pinned to the popularity of Sora and possibility that anger at the aggressive mode of unreality OpenAI is selling with it may be a tipping point.

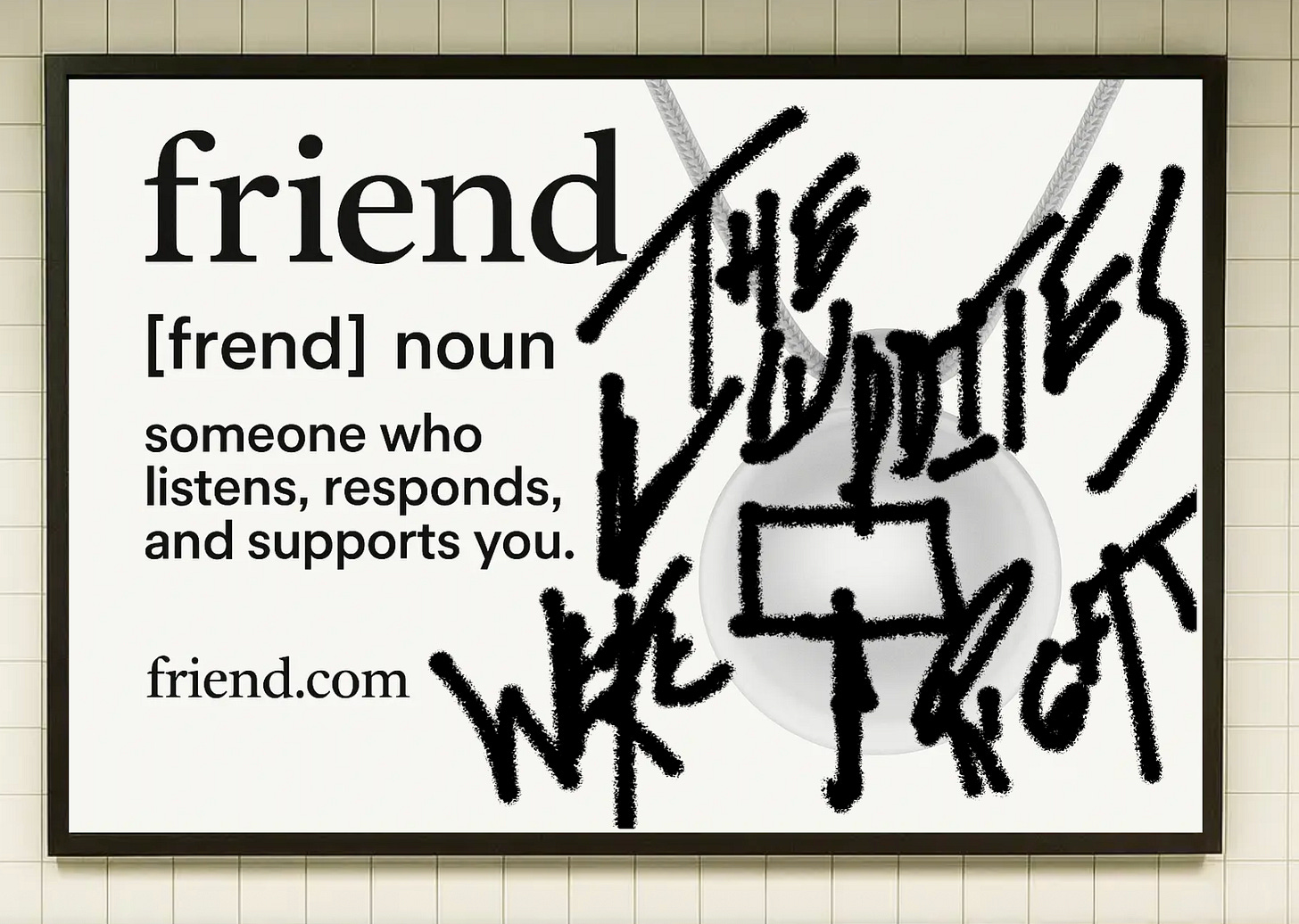

Bonus 2: A Friend ad graffiti simulator

I had to share this, too, and thanks to Alex Hanna for spotting and sharing: If you don’t live in New York City or any other major metropolis graced by the Friend billboard ads, here’s a Friend graffiti simulator with which you can vandalize the ads virtually.

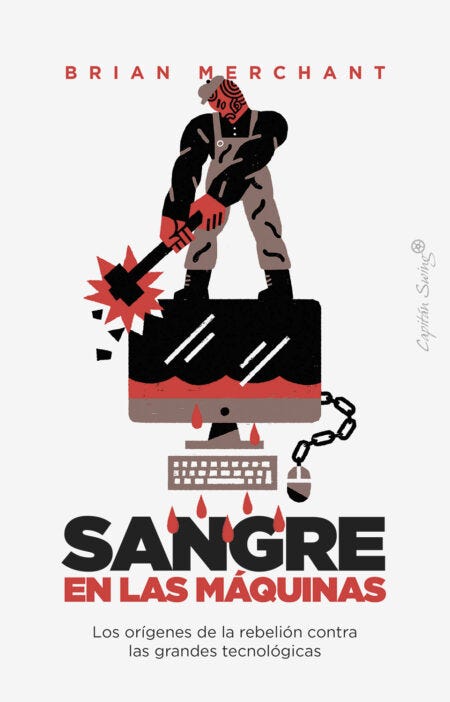

Okay, that’s it for today. Thanks as always for reading, my friends, fam, and fellow luddites; and apologies for the delay in delivery this week. Was knocked out with a cold, got behind on edits on that WIRED draft I mentioned, and then I did nonstop press for two days for the Spanish edition of BLOOD IN THE MACHINE, aka SANGRE EN LAS MAQUINAS, which publishes next week. It’s got a great cover, and the publishers—Capitan Swing, no less, named after the machine breakers who were directly inspired by the Luddites—have been amazing. (The Italian edition is out next week, too, which is also very cool.)

OKOKOK Sorry to go on again. I am very tired! But lots of good stuff along with the hellscapes, and onwards we go. Until next time.

It is well worth scanning that AMA because the CEO clearly thinks winking along with everyone is going to clear the air and no one gives him an inch of daylight, it’s just angry replies all the way down.

Another great post. I appreciated this bit most:

"There was, after all, a time in which, if a founder walked into a VC’s office on Sand Hill Road with a pitch for a big new company, and then the VC asked 'what is your company going to do?' and the founder said 'I can’t answer any questions about my company actually,' it would be clear the person was either delusional, or was trolling, and they would be shown the door. During a particularly absurd bubble around a technology with uniquely science fictional aspirations, however, investors might say, great, here is $2 billion."

Here's why: A recent article in Fast Company revealed that Andreesen doesn't make most of its money from the companies it invests in, it makes its money, like hedge fund, on the exorbitant fees it charges the investors it gets capital from. In other words, their incentive is not to support functional companies with customer-ready products and clear future profits, things a company is supposed to do; it's to attract more and more people willing to invest and pay them fees--and that requires telling these suckers a fanciful story about why customer-ready profits and future profits. So you're absolutely on point, it seems to me, that the story told about AI is far more important than any AI itself. Basically, we're not in a bubble, we're in a fairy tale.

I swear, it must be a requirement for investors in Silly Valley to have their bullshit detectors removed surgically and replaced with LLM trolling engines.

And since I want my share of the billions*

I think I’ll start a company whose mission is to build a super intelligence to hunt down the super intelligences that are dangerous to humanity. How could investors not want to throw money at that?

* No, I really don’t. I spent some years working there, and I’m not at all willing to even work *near* those people again.