Yes, the striking dockworkers were Luddites. And they won.

The ILA was derided for asking for higher wages and resisting automation. Days later, they took home a 60% raise. On the heels of the screenwriters' victory wrt AI, take note: Luddism can win.

Hello again, friends and fellow machine breakers—hope everyone’s hanging in there during this especially catastrophic stretch of October. If you’re on the east coast, especially in Florida, I hope you’re staying safe and dry. As always, I appreciate your reading, your feedback, and your support, and all those who pony up a few bucks each month to make this whole endeavor possible.

I know it’s been almost a week since the longshoremen’s strike, initially touted as a cataclysmic disaster for the US economy and potential destroyer of Kamala Harris’s presidential campaign, was resolved, and thus it is ancient history and mostly already forgotten. I would have weighed in sooner, but last week was my bday and I took some much-needed time away from the keyboard to spend with the fam, read some pulp science fiction novels, see Megalopolis, and listen to the new Blood Incantation album, and so on. It was great.

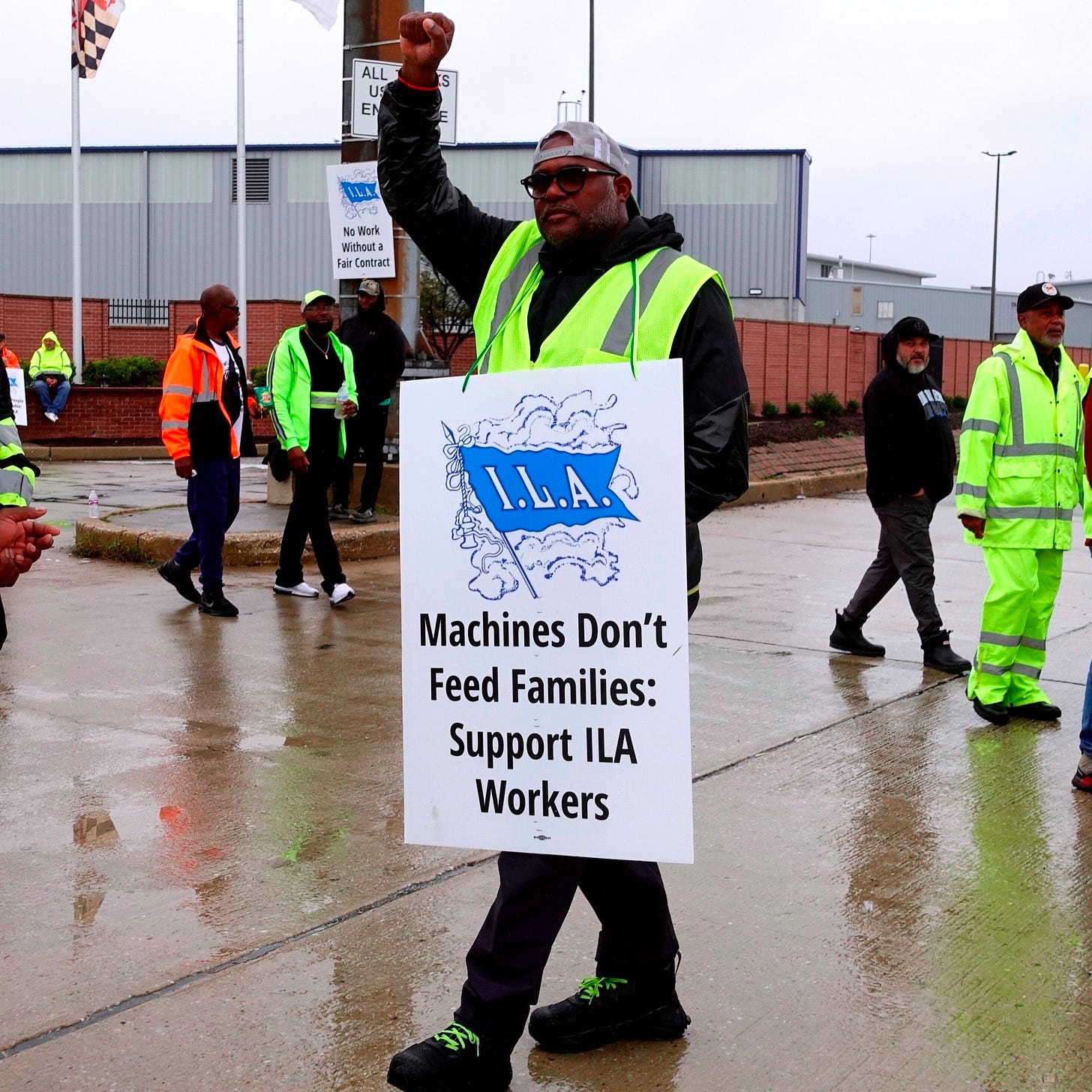

Now, naturally, there was *a lot* that drove me insane about last week’s strike coverage—and much that surprisingly didn’t! more on that in a sec—but there were two things that stood out. 1) The sheer ferocity and speed with which the workers were excoriated, not just by pro-business or conservative factions, but by liberal pundits as well1, and 2) the way the Longshoremen were condemned for their stated aim to ban port automation. Naturally, they were disparaged as Luddites.

But here’s the thing. Most of the time, as readers of this newsletter may know, the Luddite label is applied incorrectly and free of historical context, to try to paint someone as possessing a dumb knee-jerk hatred of technology, as opposed to executing a well-organized campaign for worker rights. This time, though, the shoe fit, even if it was being put on for the wrong reasons. Longshoremen were acting like Luddites—they were staging a principled, direct, and militant-flavored resistance to bosses that were hoping to automate their jobs.

And guess what? They won.

After striking for just a few days, the United States Maritime Alliance, which represents the shipping companies, and the International Longshoremen’s Association came to a tentative agreement on wages—a 62% pay increase over six years—and a commitment to resume negotiating the contract language on other issues, including automation, in three months. This despite plenty of derision and outrage over their approach from the onset, from partisan and mainstream outlets alike.

“Striking port workers are trying to fend off the inevitable,” went the headline of a story from Axios’s Emily Peck, in what was nominally a news report. (The story quotes striking union members, but the headline comes from the commentary of a shipping industry consultant.) “Why do ‘progressives’ like the dockworkers, climate weirdos and Calif. leftists all hate the future?” went a more predictably unhinged one, from the editorial board of the New York Post. And then there was the widely shared take from the economics blogger Noah Smith: “Make-work is not the future of work: The working class needs automation and upskilling, not luddism.”2

Now, no technology is inevitable—it’s the result of a series of human decisions. Opposing the use of a technology that will harm you and your peers does not mean you “hate the future”—just, perhaps, that you would like more input into how that future will unfold. And what, exactly, the future of work is should be up to all of us; especially, you know, the ones doing the work.

Furthermore, if history is any guide, the only way that the working class is actually going to benefit from automation and upskilling, is through luddism—the real kind, not the boogeyman variety in w the entirety of the worker response is made out to be smashing a machine in a rage. The real Luddites, who did not enjoy the right to vote or collectively bargain, fought not against technology, or “the future”, but those bosses who were using it to avoid longstanding laws and regulations, enable the hiring of child labor, and exploit skilled workers and drive down their wages.

By resisting those bosses who used machinery as engines of exploitation, the Luddites helped foment class consciousness, strengthened the bonds that would yield a wide-ranging reform movement, and challenged the idea that, in an industrial society, one party should be able to use machinery to accumulate profits at the expense of another, or of the common good. As historians like EP Thompson and others have shown, we have the Luddites to thank for their part in helping to seed the modern labor movement, lift bans on collective bargaining, and combat child labor—and in helping to ensure that the gains of new technologies did not accrue entirely to industrialists and that, eventually, the working class benefited from them, too. People often argue that we’re better off today, thanks to technology, than we were two centuries ago—but that’s only because groups like the Luddites fought time and time again to extend its gains to the working class.

To wit, Smith cites the port of Rotterdam, which is more heavily automated, as an exemplar: “Unions should never fight automation. Places like the Port of Rotterdam are keeping jobs and raising wages while automating everything they can, while American dockworkers' unions are trying to retreat into luddism and decay.” But the Rotterdam dockworkers have gone on strike many, many times—precisely to ensure the keeping of their jobs, and that they kept getting those raises. Those things do not happen organically, or flow from the goodness of shipping executives’ hearts.

Let’s also note here that automation does not guarantee efficiency gains, either; a 2018 study published by the left-wing rag McKinsey concluded that port automation had thus far proved to be a mixed bag, financially speaking. In ports that have automated, “while operating expenses decline, so does productivity, and the returns on invested capital are currently lower than the industry norm.” We must be careful always not to conflate “progress” or “the future” with the story corporations want to tell—in many cases automated systems cannot actually perform the jobs as well as people.

It’s also true that the ILA chief, Harold J. Daggett, makes for a uniquely unlikeable figurehead, with his rough-talking old school union guy schtick, large salary and larger house, and apparent affections for the anti-labor Donald Trump. And sure, the ask of an outright ban automation may seem tough to swallow to some. But remember that this is a negotiation; the union may be unlikely to win a full ban on automation, but why would they not start out from a position of power? They can win more on wages from there, and stand to wind up with more say over how and when automation is rolled out, and on their terms, as a result, and with a larger share of the benefits from that automation. Remember, these dock workers have made the shipping companies a lot of money for many decades; they are not “extracting rent” as the financial media likes to put it, but rather extracting a fair share of the proceeds from their labor.

That’s why the longshoremen pursued Luddism. Today, just as 200 years ago, bosses—whether a shipping magnate or a CEO of an AI company—won’t hand over the gains from a new technology to their workers willingly3. It’s why the longshoremen, as well as other unions, like SAG-AFTRA and the WGA, decided that automation was an existential threat to their jobs—and to fight back by rejecting the notion that bosses should hold the power to decide to use technology to replace their work. Outside the pundit class, these proved to be effective and popular positions, and each group won their fight, at least in the short term.

*This* is modern Luddism. Rather than allowing executives to decide who and what will be automated, regardless of the cost—human or otherwise—workers are seeing that they can reject a technology that will be used to harm them rather than submit to it. That in doing so, they may not abolish its use altogether, but gain concessions and even power over how it’s ultimately used in their working lives.

I was glad to see some in the press recognizing this, which shows something of a sea change is underfoot; outlets like the Washington Post, CNN, and even Inc. Magazine all published pieces sympathizing with the longshoremen besieged by automation—and advised workers worried about AI to pay attention. “Dockworkers are waging a battle against automation,” the CNN headline noted, “The rest of us may want to take notes.” That feeling that many more jobs might be vulnerable to automation by AI is perhaps opening up new pathways to solidarity, new alliances.

The goal is, ultimately, to render the process of automation, whether via self-operating cranes or AI-generated text, more democratic and more equitable. To this end, reader, let me tell you that I was *thrilled* to be sent this piece by kyla scanlon, who has been dubbed by Fortune “Gen Z’s favorite economist” and see her cite one of Blood in the Machine (The Book)’s key passages, about that very subject. She picks it up from there:

We can automate. But workers should be a part of it. As many others have written about we should consider labor force retraining, transition assistance, skills diversification, union-management involved with automation decisions, sharing of productivity gains and broader profit sharing, running the ports as co-ops, and new job creation within automation—these are all things that really matter as we zoom ahead with technology. We can’t just pay these people off because it’s a problem much, much bigger than just money. It’s people’s lives.

The 2024 longshoremen strike represents more than just a labor dispute; it's a microcosm of the larger societal challenges we face as we navigate the future of work in an increasingly automated world. There is a growing tension between efficiency, job security, corporate interests, and worker rights.

The path forward is not clear, but what is clear is that we need a more democratic, inclusive approach to implementing new technologies. It’s all uncertain, creating ripples that can be harmful in the long run. Nothing can be smooth sailing, but the key is to support workers through changes, not just replace them with machines.

Hear, hear.

I suspect that the only way that many of those things will be meaningfully achieved is with aggressive labor action, more determined organizing, and strong laws governing automation. As such, contrary to Smith’s advice, that unions should never fight automation, I would argue that unions—and workers in general—should always fight their bosses over automation. If, that is, they rely upon or have any affection for their jobs. Automation is, after all, primarily adopted for one simple reason: To try to save management money on labor costs. If it is not contested, the automation process made more democratic—typically but not only through collective bargaining—then those saved labor costs will come at the expense of a worker and/or their job, and the gains will be sent swiftly upstream.

Luddism does not stymie progress, contrary to popular belief, nor does it lead to make-work. It allows working people to help shape the way they want to see technology enter and inhabit their working lives. It gives them a voice, and if that voice says no, there’s probably good reason, and we should listen. In an era where we are beset by automation, AI, and a flood of scarcely vetted and potentially harmful technologies, it’s more important than ever that we all learn to use that voice.

The WGA and the longshoremen acted like Luddites—and they won, for now, higher wages, and greater control over the technologies that govern their lives. The columnists were right, more workers might take note. The new Luddites can win.

This was a predictable if uglier-than-usual iteration of a ritual we often see when just about anyone protests, walks out, or goes on strike: The Shaming of the Workers Who Dare to Ask for More. Hamilton Nolan touched on this in his writeup of the strike last week, and it’s indeed a sign of how successfully the idea has been beaten into us that American workers are lucky to have any job at all—much less a good one, that doesn’t even require a college degree—that when some of those workers withhold their labor, the knee-jerk reaction among many is to heap scorn on them. We got TikToks of men yelling at workers on the picket line, economy wonks furious about the inefficiencies these workers dare produce, and pundits wringing their hands over the impact these workers might have on the election. We heard a lot about the “six figure” salaries some dockworkers earn (after reaching seniority and doing lots of overtime) and the $800,000 salary the ILA union chief commands and his big house in New Jersey. We didn’t hear as much about the CEOs and owners of the shipping companies. Or how the shipping industry generated $400 billion in profits over the last four years—exceeding, astonishingly, the combined amount that the industry earned over the last four decades, per CNN. Or how all that made shipping magnates, some of the richest men in the world, even richer.

This part of Smith’s post struck me…

We should all be thinking very hard about whether it’s wise to have a labor system that can allow that sort of thing to happen. Is it right that the livelihoods of millions of Americans should hang on the whims of 50,000 dockworkers? Is it smart to give a single union the power to shut down a large portion of America’s critical infrastructure? Collective bargaining is important, but there should be limits on how destructive we allow that bargaining process to be…

… and made me want to try a little experiment here: What if we just tweaked this sentence like so, how would we feel about this?

Is it right that the livelihoods of millions of Americans should hang on the whims of 50,000

dockworkersCEOs?

That there is a cohort of people that holds the fate of millions of workers in their hands every day doesn’t really bother anyone until it is a group of working people, it seems to me…………..

Note the ever-shrinking number of times Sam Altman and his cohort even mention things like universal basic income anymore, which once accompanied their pitch for technologies that they claim can eliminate lots of jobs.

Brian, have you written about the longshore unions' Mechanization & Modernization Agreements? Everything you've written here applies to it — Harry Bridges, the west coast ILWU leader, saw technological change was coming to shipping and led his union (and later the allied east coast ILA) to put in place a framework that would result in certain longshore workers being among the best paid union workers in the world. It's the process you describe writ large, at least large enough to cover the last 65 years.

That Luddism won for the ILA is true to the extent that workers will have a democratic say in the work process. Currently they have NO agreement on automation although this was their main sticking point during the strike. During the ILWU contract negotiations in 2022 ILA leader Harold Daggett even made a point of slamming his fist on the table saying they would accept NO automation at East Coast terminals. They got 60% raise under a Tentative Agreement which is something progressive for them as they have long lagged behind the West Coast on wages and benefits. The point of worker resistance to automation is not to fight technology itself as you point out, but to get more democratic control over the work process. During the Mechanization and Modernization Agreement effecting the ILWU in the 60’s and 70’s, a leading opponent of this agreement by the name of Stan Weir advocated a Modern Day Luddism. You can find his writings online available for free pdf download at Libcom. I have been a Merchant Seaman with 15+ years experience seeing the global supply chain in practice, and now a Stevedore in West Coast ports. I feel the best way to advocate more worker control as Luddism entails is to join our efforts along with the cause of radical ecological change. The writers strike over AI entailed a struggle over the preservation of human creativity. For industrial workers, particularly in transportation, our struggle against “the machine” entails the reality of ecological collapse as long as giant container ships carrying manufactured goods across the Oceans persist. Descaling these gigantic entities that dominate the supply chain such that local control over the effects of pollution and having worker greater participation would be the ultimate goal.

Joel Schor

Member - International Longshore and Warehouse Union ILWU local 10, Former longtime and retired member of Sailors Union of the Pacific SUP.