Understanding the real threat generative AI poses to our jobs

There will be no robot jobs apocalypse, but there's still plenty to worry about. How *will* generative AI impact our jobs?

Hello, and welcome back to Blood in the Machine: The Newsletter. (As opposed to Blood in the Machine: The Book.) It’s a one-man publication that covers big tech, labor, and AI. It’s all free and public, but if you find this sort of independent tech journalism and criticism valuable, and you’re able, I’d be thrilled if you’d help back the project. Enough about all that; grab your hammers, onwards, and thanks for reading.

According to Elon Musk, AI is about to take everyone’s jobs. Soon, “probably none of us will have a job,” the tech billionaire said at a recent tech conference in Paris. “If you want to do a job that’s kinda like a hobby, you can do a job. But otherwise, AI and the robots will provide any goods and services that you want.”

This is conventional wisdom among many Silicon Valley honchos — the week before Musk made his comment, Geoffrey Hinton, the so-called godfather of artificial intelligence and former Google Brain employee, said he’s worried that AI will take so many jobs that he’s lobbying the UK government to enact a universal basic income. Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, has repeatedly spoken of the mass job loss products like his will bring forth. The list goes on.

And yet, the biggest AI story at the time that Musk was predicting mass robot replacement was the anarchic meltdown of Google’s new ‘AI Overview’ product, which was spewing bad, unhinged and demonstrably false answers with gusto. There are no African countries that begin with ‘K’, according to Google’s AI results, a good pizza recipe includes glue, and Barack Obama was the first Muslim president. Hardly, some might argue, evidence of an unstoppable super-intelligence on the rise.

Meanwhile, we’re seeing more headlines like this: “Generative AI may be creating more work than it saves.” Or this one: ”Amazon, Google Quietly Tamp Down Generative AI Expectations,” from an Information story about the tech companies’ internal fears that AI is underperforming. Or: “We may not lose our jobs to robots so quickly, MIT study finds.” Companies that have embraced generative AI for business purposes have realized that AI output is frequently unreliable, that it’s often unclear where AI can be usefully deployed in existing workflows, and that questions of whether the systems are secure enough for corporate use, or if they might violate copyright laws, remain largely unanswered.

So which is it? Is generative AI going to be widespread in offices and businesses across the world, and highly disruptive to our jobs? Or is it an overhyped dud that generates dubiously usable output, and isn’t up to the task of actually replacing human workers? The answer, unfortunately, may be “both,” with a heavy side of “it all depends.”

This is why I think it’s crucial that we try to understand the actual threats posed by generative AI — beyond the self-serving jobs apocalypse forecasting of certain tech CEOs and pundits. (Who stands to profit, after all, from the rise of job-stealing software that costs a monthly fee to license?) I know a lot of people are genuinely afraid about the impact of AI on their jobs. Out on book tour, it’s the number one question I field: How worried should I be? People are concerned about the products sold by OpenAI, Midjourney, Anthropic, and quite justifiably so. Lots of executives and managers, maybe even your very own boss, are listening to these companies’ sales reps as we speak! So the very first thing to understand is that, regardless of how this is framed in the media or McKinsey reports or internal memos, “AI” or “a robot” is never, ever going to take your job. It can’t. It’s not sentient, or capable of making decisions. Generative AI is not going to kill your job — but your manager might.

Given that, I thought it might be helpful to share my read on The Generative AI Jobs Question, based on my research into the first major wave of industrial automation — and the clothworkers and artisans whose jobs were most impacted — as well as my recent reporting on how AI is shaping work in a number of fields today. Note that this is explicitly *not* a “how to supercharge your work with AI” business management article, there are plenty of those out there. This is for everyone else, for anyone who may not be interested in becoming an AI power user but is interested in the real effects a widely hyped new breed of productivity software might have on their working lives.

This is gonna go a little long, so for those of you who want the TLDR, here goes:

-If history is any indicator, there’s no catastrophic, Great Depression-level mass job loss event on the horizon, BUT

-That won’t stop bosses from trying to use AI to replace certain jobs, keep pay lower, and demand you and your coworkers produce more work

-Your bosses’ measuring stick for AI output isn’t whether it’s so good it can replace you wholesale, but if it’s “good enough” to justify the savings on labor costs

-Certain industries *are* uniquely vulnerable to generative AI output, and are more threatened than others

-After workplaces are disrupted by generative AI, employees not laid off or reassigned will have to pick up the pieces, often with more work than before

-Whether or not your boss adopts generative AI directly or your industry is threatened, the technology can be used as leverage against you and your colleagues

-Generative AI may or may not be a flash in the pan, but it can be a wrecking ball to your job regardless, especially if your boss is looking for an excuse to cut costs or to appear innovative — and you should be ready

There will almost certainly be no AI jobs apocalypse. That doesn’t mean your boss isn’t going to use AI to replace jobs, or, more likely, going to use the specter of AI to keep pay down and demand higher productivity

Throughout industrial history, there are few examples of a new technology being used to immediately wipe out entire job categories wholesale. As the sociologist and automation researcher Aaron Benenav has told me; it’s *possible* that such a thing could happen, but it hasn’t really happened before, and it’s highly unlikely it will happen now. (Especially with tech as patchy and unpredictable as generative AI.) Most, though not all, human jobs are too hard to do, too embedded in organizational makeup to wipe right off the map, even if plenty of businesses would love nothing more to do exactly that. Indeed, fully-automated factories have been a dream of entrepreneurs since the 1800s. In practice, bosses tend to use automation technologies to keep wages down, deskill workers so they can hire cheaper, more precarious ones, and demand more output for the same price.

Take the first Industrial Revolution. Factory owners did not invest in mechanical looms and wipe out weavers entirely — they still very much needed humans, often children, to operate those more mechanized looms — but they did squeeze them, and mass produce cheaper, lower quality goods. The clothworkers didn’t disappear, but their pay, security, and quality of life sure did. And certain specialists in the industry, like cloth finishers, were ultimately replaced almost entirely by machinery. This is why the machine-smashing Luddites took up hammers in the 1810s — not because they hated technology, but because bosses were using it to tear apart their livelihoods. (And it’s perhaps worth noting that, to this day, cloth making is far from fully automated; clothes are manufactured with loads of human labor in often precarious conditions around the world.)

This tracks with what’s happening with generative AI now: OpenAI says 92% of Fortune 500 companies are already using ChatGPT. If management can uncover places where it can effectively replace a worker with generative AI, you bet they’ll try. And there have been a few companies, like the financial services firm Klarna, that have announced they’re saving huge sums in labor costs — $10 million in marketing, according to the CEO — by switching to generative AI. (Whether or not those savings are real or sustainable is another matter.) But most have been slower to move, for the aforementioned reasons (unreliability, security concerns, lack of real efficiency gains), and others. MIT Tech Review Insights surveyed 300 business leaders, and 75% said they’d experimented with the tech, only 9% said they had “adopted the technology widely.” Yet executive ambitions remained unconstrained; 85% of those leaders expect to use generative AI to automate ‘low value’ tasks by the end of the year.

In other words, if you’re thinking about how generative AI might be used in your workplace, you don’t want to default to either of the two poles: You do not need to worry that a freshly sentient AI is going to take your place at the office, nor should you write off AI as a complete nothing. All it takes is for your boss to be sold on the idea of AI, to get it in his head that it will allow him to initiate downsizing, or to rely more on outsourcing or contract labor,

This is exactly why AI companies, especially OpenAI, strive to create the impression that their products are so powerful that they’re frightening, portending a jobs apocalypse is part and parcel of that effort. Executives, managers, bosses need to believe the tech is powerful enough to be humanlike, and thus, save them some human labor costs.

Your boss isn’t concerned with the philosophical question of whether generative AI is so good it can replace or replicate human workers, your boss is concerned with whether its output will be ‘good enough’

If you talk to workers who’ve encountered generative AI in their workplaces, or even pushed back against it, you might have heard about the specter of ‘good enough’ tech. Few coders, writers, artists, creatives, or authors are worried that AI will be better, or even as good as they are, at their jobs: The fear is that gen AI will be deemed “good enough” by management to substitute for their work, at a cost savings. That’s the threshold.

Back in the Industrial Revolution days, the garments churned out by early automated machinery — often operated in factories by children and migrant workers — didn’t hold a candle compared to what the skilled clothworkers of England produced. They were less expensive, shoddier, and fell apart after repeated use. That was a big reason the clothworkers hated the machinery so much: those cheaper, inferior garments lowered prices for goods across the board, and damaged the reputation of the region-based industries.

The mechanized looms and mills were “good enough.” And that’s the fear. Which brings us to the next point:

Generative AI is likely to be extremely disruptive to atomized, freelance, and precarious creative labor

While there’s unlikely to be mass job loss on a scale that would worry economists, there is a very real threat that it will be absolutely pernicious to a number of fields, especially creative ones. Here’s a partial list of occupations in which I know people have already either lost work or entire jobs, because I’ve spoken to them or their colleagues directly:

-Illustrators

-Copywriters

-Marketers

-Concept artists

-Graphic designers

-Customer service

-Asset artists

-Content creators

-Transcribers

-Translators

Illustrators I’ve interviewed have already seen the number of corporate clients hiring them for work take a nosedive. Some artists tell me they’ve lost as much as 50% of their corporate work since the start of the generative AI boom. That’s because image generation is uniquely vulnerable to automation — if, that is, a client or corporation isn’t concerned with potential copyright violations or diminished quality. An image, after all, can’t be *wrong*, it just needs to look good, or, ominously for the illustration field, “good enough.” If a corporate client needs some internal art for a pitch deck, a presentation, or a company brochure, Midjourney can deliver, especially if it’s not public-facing and they’ll never risk taking any flack for it.

Copywriters are losing jobs, along with content producers and marketers. Sports Illustrated, VICE, and CNET have all been hollowed out, lost hundreds of employees, and been taken over by private equity or third party content firms that use AI to mass produce SEO-optimized blogs.

Translators and transcribers have been hit hard for years, thanks to Google Translate and AI transcription services like Trint; generative AI is accelerating the process. They’re both industries vulnerable to the “good enough” principle — no one would rely on AI for the translation of a novel, or the transcription of, say, a hearing being entered onto the public record; at the very least a human would need to check the results. But the AI systems take work with lower stakes, drive down rates, and shift the status of jobs from translators to AI translation-checkers.

This, notably, was precisely what the Writers Guild screenwriters were fighting against in their strike, when it came to AI. They knew the studios couldn’t use AI to produce great scripts, but they also knew they might want to use it to spin up mediocre ones — and ask writers to punch them up for reduced fees and no share in the residuals. The WGA writers, however, had a union, and the ability to win a contract that guarantees that studios can’t do that — most illustrators, copywriters, and creatives do not. That’s why these workers are the most vulnerable to AI of all, and the fields I really, truly worry about.

As much as we all love to dunk on the dumb errors and low-grade AI art the generators churn out, ultimately, companies like Klarna, that are looking to cut labor costs to the bone, won’t care. Then other companies will wonder why they’re still using human art if Klarna’s got this competitive advantage, and presto, we have ourselves a depressing race to the bottom in a vital artistic profession. This is why we laugh at our own peril.

Because remember, this is what many bosses 100% hope to do. The AI analyst Azeem Azhar recently recalled being in a meeting with 100 CFOs who were discussing the promise of generative AI to cut labor costs. “Let’s just say they were like cats surrounding a group of baby starlings — and let’s just say the lips were being licked,” he said. There were of course plenty of managers and executives on the lookout for new and innovative ways to reduce headcount before generative AI came along; the new technology gives them an opportunity to report savings at the next quarterly report and a chance to show they’re embracing the cutting edge — better still, if ChatGPT-4 underperforms and it’s all a major disaster over the next two years, well it’s not their fault. All that it really costs them is some people’s jobs.

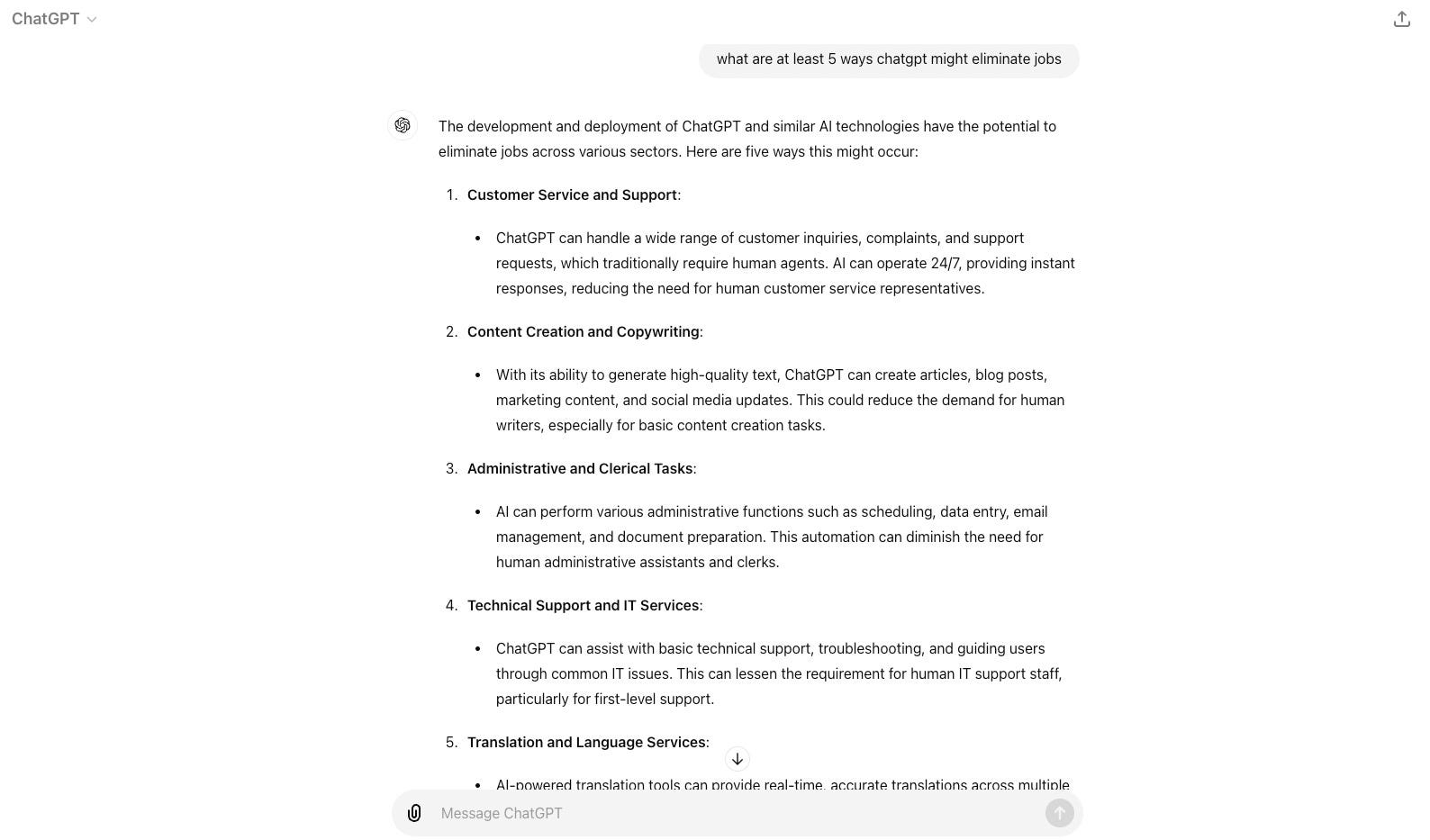

To wit, if you prompt ChatGPT about the kinds of jobs it might eliminate, the response it generates reads as an advertisement.

But despite the bold claims, don’t expect a smooth ride if your boss brings enterprise AI into the workplace.

Generative AI may result in you having to pick up more work, not less

So the line around automation and AI is always that it’s supposed to make our lives easier, and free us up to do more liberating, creative work. The AI is supposed to do the three D’s — our dull, dirty and dangerous jobs — saving us time and displeasure in the process. In reality, any efficiency gains created by the tech are all but sure to be captured by management (this is why they are investing in it, of course) and you’ll find yourself doing more of the rote work than before.

How can I be so sure? Well, this is what has happened approximately 99.9% of the times in our industrial history when companies embrace automation, from the cotton mills of the 1800s to the computer revolution that began in the 1960s. In 1930, John Maynard Keynes, probably the most influential economist of the 20th century, looked at the trends in technological advancement and productivity gains and predicted his grandkids would enjoy a 15 hour workweek. That, suffice to say, has turned out not to be the case.

Keynes’ error was overlooking how aggressively elites would capture the economic gains realized by all that productive technology. Most of us know that story pretty well; we’ve lived it. Real wages have stagnated for working people for decades — starting around the time that we were promised computers would serve as gateways to prosperity by unleashing our personal productivity and eliminating busy work the first time. (In fact, the only way to be sure that you receive the benefits of automation technologies in your workplace may be to not tell anyone you are using them.)

This is maybe a long-winded way of saying, if your department gets downsized, don’t be surprised if management expects you to pick up the slack with an AI tool. I’ve spoken to multiple people in different fields (consulting, design, gaming, etc) who have seen precisely this happen already. In some cases, in weeks following a department-wide layoff, management has sent out emails about Copilot training sessions that remaining employees are expected to attend. It’s not necessarily a 1-1 replacement, but management’s underlying expectation is that generative AI can make up for lost productivity — and it may encourage more managers to pull the trigger on layoffs, in the first place, or to allow more attrition to take place.

Furthermore, studies have shown that the introduction of automation technologies can be a nightmare for the workers who remain: They’re expected to not only shoulder a larger burden of the work, but to check the new technology’s output to ensure it’s not messing up. A study of supermarket self-checkout kiosks found that the technology, which management used to justify firing workers, added a major burden to remaining checkout workers, who had to man their own aisles as well as helping angry customers with the new systems.

With generative AI, it’s similar — hospitals have responded to staffing shortages by implementing AI that they say can help diagnose patients and prescribe medicine. And nurses working with it say it’s been an utter disaster; they’ve had to work overtime just to make sure it’s not making mistakes that could endanger patients’ health.

Even if it’s not being prominently used, generative AI can be used as leverage against workers just about anywhere

The anxiety over AI itself can be harnessed by management as a powerful tool. Much the way restaurant CEOs raise the prospect of automating fast food workers’ jobs with robots when they began demanding $15 an hour and a union, generative AI is an omnipresent lever now at the disposal of bosses just about everywhere.

It is an ambient, omnipresent threat to job security — whether it actually can be deployed in a use case or not. As with many of the cases described above, a manager may not even seek to deploy this tool maliciously; some will, some won’t mention it much at all.

But suffice to say that executives both pitching and buying enterprise generative AI systems are well aware of this creeping anxiety. If a firm or a manager makes it known that it has purchased a premium tier AI system, or even that it is exploring the technology, or is experimenting with an in-house AI system — it’s likely to yield a chilling effect on anyone who might feel insecure with their job status already. The mere presence of these systems, in many cases, can discourage people from asking for raises, from organizing, even from speaking up on workplace issues; there’s an AI waiting in the wings after all, and we know well why they were purchased.

In some fields, the disruption wrought by generative AI may be temporary. The tech might not pan out. You should still be prepared.

As I’ve argued on this very newsletter, AI is at a critical and fascinating juncture — I called it AI’s smoke and mirrors moment. Not because it’s all an illusion devoid of real substance, but because it’s a consumer technology that has been elevated by showmanship and hype, with eye-catching demos and tech titanic myth-making, and all of that is in search of a home run product use case.

The greatest bet seems to be on enterprise-tier functions — OpenAI just sold 100,000 memberships to the consulting firm PwC, and has said it had approximately 600,000 before that. That’s a lot of prospective task and job automating, and that’s just OpenAI; Microsoft’s Copilot is doing reasonable business too, and Anthropic’s Claude Team and Cohere’s R+ systems are in the mix as well.

Yet AI scientists like Melanie Mitchell repeatedly caution that we need to be intensely skeptical of claims that, say, LLMs are better than humans at basic tasks. And it appears, as noted by the cognitive scientist Gary Marcus and others, that the AI models aren’t improving as fast as they had in the past — they may in fact be plateauing. If that’s the case, then a lot of these models will be stuck at reliability rates of around 80% — enough for noncritical text and image generation, but nothing a serious business would want to rely on for important documents or public-facing materials. It may well be that all these businesses that have bought into the enterprise tier AI systems use them for a few months to a year, and discard them as the hype dies down.

Again we see why it’s crucial that hype is maintained at near-apocalyptic levels; if it’s not getting results for a certain use case, well maybe I’m just not using it right? This is the anointed technology right now, and Microsoft, Google, Meta, and $100 billion of valuation couldn’t be wrong, right? If that hype drifts away, we may be left with an impressive but quirky technology, largely trained on the work of artists and writers who were not paid or consulted, and that has a few niche use cases for automating away the ones still currently trying to make a living. Considering how expensive and resource intensive the technology is to run, well, that’s not going to be worth $100 billion, and it could all fall to earth — and take a hell of a lot with it in the process.

Yet there’s a big difference between the metaverse, web3, crypto, and the other recent flash in the pan tech trends; executives, investors, salesmen, bosses, consulting firms, and middle managers everywhere are dying for this to pan out. But even if it doesn’t, and the systems peak and fail hard at too many tasks to be viable, we could still be looking at some pretty painful short-term disruption.

So my manager’s announced our company is implementing AI — what to do?

Formally or informally, get organized. If your boss is bringing AI to your department, talk with your colleagues. So many of the problems we’ve seen arising from technology in our recent industrial history come because it’s imposed from top-down, not democratically. Often there’s nothing you can readily do about a mandate to use a new software in your job; sometimes, there is. Presenting a unified front with coworkers and colleagues makes it more likely your concerns will be taken seriously.

Don’t be afraid to push back on certain use cases, or point out that the output of generative AI is unreliable, insecure, and potentially at risk of copyright violation. Or that in the past, hasty adoption of automation has not only hurt employees, but the customers, the company, and the bottom line. (That’s what ultimately happened with the early self-checkout kiosks, they were such a lose-lose-lose that some companies that adopted them shipped them back.)

In a lot of fields, from tech to gaming and beyond, AI is starting to spark more conversations about unionizing — the WGA’s success made clear that workers stand to have more power over how AI is used in their workplace if they’re organized. With AI looming, it’s a good time to have those conversations in your workplace, too; we need to do all we can to establish worker consent over AI, and the best way to do this right now is through a union.

Freelancers: You already know this, but you’re the most vulnerable. You can only guess at why you’re not getting as much work, or read between the lines on those emails when your contacts say there are currently no gigs to be had, or apologize that pay rates have fallen. There are groups out there that can help, on top of your own whisper networks — the Freelance Solidarity Project is a good place to start. It’s imperative that freelancers start building power right now, because they’re working in the most threatened fields, at the greatest risk of seeing their work not only fed into maw of a corporate LLM, but then used to try to automate away your livelihood.

Support the class action lawsuits against the AI companies. Get involved. Reach out to colleagues. Talk about organizing. You and your colleagues may decide that there are some valuable use cases for the AI systems — given that the ethical issues are addressed and resolved — decide together, how you might consent to use the systems. But if we don’t want management to use generative AI to chew up the things we find most valuable in our jobs — or the whole job altogether — we may well have to push back. To resist.

And when you do, you’ll probably be surprised at just how many others are willing to push back, too. The striking screenwriters drew shocking levels of support, despite being ‘Hollywood elites’, precisely because they tapped into most everyone’s anxieties about being steamrolled by AI. We all can tap into that, too.

Because left alone, Sam Altman, Elon Musk, their tech exec cohort, bosses, and middle managers will be all too happy to try to realize their dreams of total robot replacement — to use AI to automate your work, keep your pay down, whittle away at working conditions, and assert more control over your working life. The introduction of generative AI in your workplace may not always seem like a big deal, and in many cases it won’t be — in others, it could be a wrecking ball. Stay frosty out there. And don’t be shy; I’m happy to talk about issues of AI in the workplace just about anytime, anywhere. Leave a comment below or shoot me a DM or an email.

Remember, we don’t have to sit here and let enterprise generative AI run roughshod over our lives — we can, and should, fight back. Unlike the Luddites, we don’t even need hammers. Yet.

Small but important note -- even if you don't have a union, if you and your coworkers *collectively* take some form of action (e.g. a jointly signed letter to management expressing concern about poorly-implemented AI), that is still legally protected by labor law, so it would be illegal for your employer to engage in any kind of retaliation. It's called "concerted activity" if you wanna get technical about it, but the legal standard is basically "do something with at least one other person."

> "Who stands to profit, after all, from the rise of job-stealing software that costs

> a monthly fee to license?"

As well as being about as reliable as a Yugo's transmission. And who has to fix the problems? PEOPLE! And just as people need time off for vacations and illnesses, software "takes time off" when it's down. These idiots who want to fire everyone and just use software doesn't understand that.

I know someone whose company went all out a few years ago with getting all sorts of time-saving, money-saving software. They laid off 25% of their workers. Now they have more problems than they can count, are far behind, and are spending much more money (on software) to achieve the same results. Last December for the first time ever they could not pay out bonuses because all their money went to fixing the software that was going to save them all that money. And this is "reputable" software, from companies like Salesforce, Oracle and Google. At conferences they talk to others in their industry who tell the same story, so it's not just them. When I asked my friend why they did this when it was clearly a losing move, she replied, "Because everyone else [i.e., their competitors] is doing it." Brilliant. Reminds me of Apple's infamous "Lemmings" commercial. It angered people who saw it, but Apple told the truth, and everyone hated them for it.