AI really is smoke and mirrors

Just not in *exactly* the way you might think.

Hello, and welcome to Blood in the Machine: The Newsletter. (As opposed to, say, Blood in the Machine: The Book.) It’s a one-man publication that covers big tech, labor, power, and AI. It’s free, though I’m in the process of ramping up to be less occasional, so if you’d like to support this brand of independent tech journalism, and I’d be thrilled if you’d consider pledging support — I’m considering going paid, and seeing how much interest might be lurking out there would be a big help. But enough about all that; onwards and upwards, and thanks for reading.

This might well be the most fraught moment in generative AI’s young lifespan. Sure, thunderous hype continues to emanate from Silicon Valley and echo across Wall Street, Hollywood, and the Fortune 500, and yes, de facto industry spokesman Sam Altman is pursuing ever more science fictional and GDP-of-a-G7-nation-sized ambitions, heralding the coming of a nascent Artificial General Intelligence all the while, and indeed, the AI bulls blog away, insisting someone using AI is about to take your job — so don’t get left behind.

And yet. We’re over a year into the AI gold rush now, and corporations using top AI services report unremarkable gains, AI salesmen have been asked to rein in their promises for fear of underdelivering on them, an anti-generative AI cultural backlash is growing, the first high-profile piece of AI-centered consumer hardware crashed and burned in its big debut, and a bombshell scientific paper recently cast serious doubt on AI developers’ ability to continue to dramatically improve their models’ performance. On top of all that, the industry says that it can no longer accurately measure how good those models even are. We just have to take the companies at their word when they inform us that they’ve “improved capabilities” of their systems.

So what’s actually going on with AI here? We’ve got a still-pervasive cloud of buzz, aggressive showmanship, and an intriguing if problematic technology, whose shortcomings are hidden, increasingly haphazardly, behind the lumbering hype machine. We’ve heard the term snake oil used to describe the generative AI world’s shadier products and promises — it’s the title of a good newsletter, too — but I think there’s a more apt descriptor for what’s going on in the industry at large right now. We’re smack in the middle of AI’s smoke and mirrors moment, and the question is what will be left when it clears.

Now, look; I don’t mean this entirely derisively. I do recognize that we understand the phrase ‘smoke and mirrors’, whose modern coinage apparently comes from a journalist writing about Nixon, to describe an elaborate illusion that ultimately holds no substance at all. What’s happening here is a bit more complex.

We are at a unique juncture in the AI timeline; one in which it’s still remarkably nebulous as to what generative AI systems actually can and cannot do, or what their actual market propositions really are — and yet it’s one in which they nonetheless enjoy broad cultural and economic interest.

It’s also notably a point where, if you happen to be, say, an executive or a middle manager who’s invested in AI but it’s not making you any money, you don’t want to be caught admitting doubt or asking, now, in 2024, ‘well what is AI actually, and what is it good for, really?’ This combination of widespread uncertainty and dominance of the zeitgeist, for the time being, continues to serve the AI companies, who lean even more heavily on mythologizing — much more so than, say, Microsoft selling Office software suites or Apple hocking the latest iPhone — to push their products. In other words, even now, this far into its reign over the tech sector, “AI” — a highly contested term already — is, largely, what its masters tell us it is, as well as how much we choose to believe them.

And that, it turns out, is an uncanny echo of the original smoke and mirrors phenomenon from which that politics journo cribbed the term. The phrase describes the then-high tech magic lanterns in the 17th and 18th centuries and the illusionists and charlatans who exploited them to convince an excitable and paying public that they could command great powers — including the ability illuminate demons and monsters or raise the spirits of the dead — while tapping into widespread anxieties about too-fast progress in turbulent times. I didn’t set out to write a whole thing about the origin of the smoke and mirrors and its relevance to Our Modern Moment, but, well, sometimes the right rabbit hole finds you at the right time.

The original smoke and mirrors

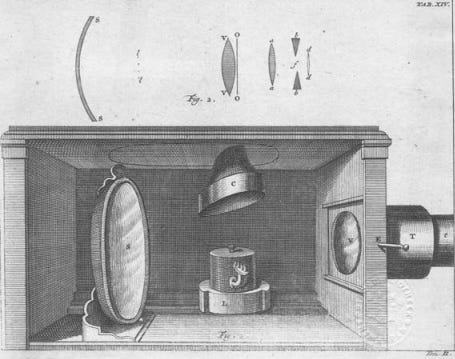

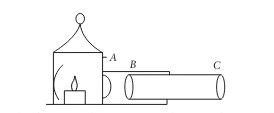

In the 1660s, an inventor, probably, according to scholars, one Christiaan Huygens, created the first “magic lantern.” The device used a concave mirror to intensify the light of a candle flame to project an image printed on a slide through a tube with two convex lenses, thus amplifying that image on any nearby flat surface.

This was a profound technological advance. For the first time, an intangible image could be made “real.” According to the science historian Koen Vermeir, whose wonderful 2005 paper, “The magic of the magic lantern (1660–1700): on analogical demonstration and the visualization of the invisible”, has consumed many of my afternoon hours,

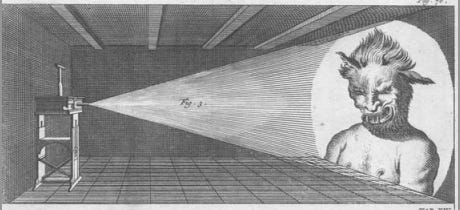

“The projected image was new to most spectators and was a reason for bewilderment. The shadowy projections on the wall resembled dreams, visions or apparitions summoned up by a necromancer, and the devil was widely regarded as the master of such delusions. The effect of strange apparitions was further enhanced by the depicted subject; the prominent theme which leaps to the eye is the monstrous, and monsters, demons and devils were the highlights of the show. Indeed, the typical illusionist capacity of this new apparatus was best accentuated by projecting the ‘unreal’. It was the first time that a fantastic and fictional image could be materialized, without becoming as solid as a picture.”

You might already see where I’m going with this. Last year, when OpenAI released ChatGPT, the reaction among the media and users alike often transcended mere excitement over a new tech product — the New York Times’ tech columnist Kevin Roose said he was “deeply unsettled” that a chatbot had tried to break up his marriage, and users, who fast multiplied into the tens of millions, reported being “freaked out” by the bots; one user reportedly took his own life upon the bots’ recommendation.

But the devil isn’t behind these such delusions — that would be the concept of AGI, the all powerful sentient machine intelligence that top AI industry advocates insist is taking shape before our eyes. Silicon Valley leaders’ constant invocation of AGI, paired with years of more generalized and deterministic insisting that AI Is The Future, lends a gravity to the technical systems, known as large language models (LLMs), that really have gotten pretty proficient at predicting which pixel or word it should fill in next, given a particular prompt.

The LLM is like the magic lantern that gave us the first smoke and mirrors in a few other ways, too. Here’s Vermeir again, noting that the magic lantern

… embodies the intersection of mathematical, physical and technical ‘sciences’. It mediated between educated, popular and courtly cultures, and it had a place in collections, demonstration lectures and texts. In the secondary literature, the magical qualities of the lantern are often unmarked or taken for granted. The magic lantern is taken as an ancestor of cinema, as an instrument in a demonstration lecture, or as a curiosum provoking wonder.

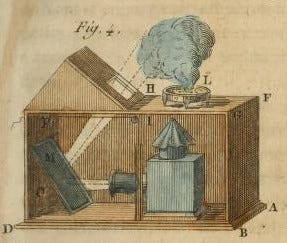

Yet the lantern probably became most famous for giving rise to phantasmagoria — demonstrations, seances, and horror shows that deployed one or more of the devices, along with that titular smoke, to create scenes where the images appeared to be floating in thin air; often accompanied by sound effects and dramatic narration. The technology was embraced by illusionists and magicians, and, naturally, by grifters who took the tech from town to town claiming to be able to conjure the spirits of the underworld, for a fee.

Importantly, audiences were not simply open to believing in the illusion out of the sheer novelty of the experience, or even its rather capable powers of confirmation bias, but thanks to the mounting social instability and political upheaval going on around them. As Vermeir notes, “social uncertainty and anxiety were expressed in a cultural fascination for illusion.”

In fact, some of the most famous phantasmagoria shows in London were held in the first decade of the 19th Century, and by then they included elaborate automata and other mechanical instruments — just as the conditions that would give rise to the fury of the Luddites were ripening. (Sometimes you stumble onto something so ripe with resonance you wish you could go back and add it retroactively to your book — would love to be able to add in a bit about phantasmagoria and magic lanterns to Blood in the Machine, but alas).

Veirmeer describes what the magic lanterns allowed its operators to do as “analogical demonstration.” The new technology allowed its operators to create a more convincing vessel for demonstrating an abstract, even unprovable, concept or a force. Not all of the public believed they were seeing emanations from the beyond, or that they were seeing proof of a divine world, but the power of the technological demonstration helped articulate and underline those beliefs nonetheless.

You don’t want to put too fine a point on historical parallels, and the contexts in which generative AI and the magic lantern were developed and deployed were clearly quite different — but there’s plenty to chew on here. The science historian Veirmeer, in his conclusion, notes that the lanterns “could shift from magical contexts to natural philosophy, and sometimes the borderlines are far from clear… They were analogical demonstrations of undemonstrable philosophical principles.”

I love that phrase. Incidentally, it’s a pretty good way to describe how chatbots and image generators function for AI executives and true believers in AGI: as “analogical demonstrations of undemonstrable philosophical principles.” After all, there is no scientifically determined point or threshold at which we will have “reached” or “achieved” AGI — it’s an ambiguous conceit rooted largely in the ideas of technologists, futurists and Silicon Valley operators. These AI-produced images and videos, these interactions with chatbots and text generators, are analogical demonstrations of the future those parties believe, or want to believe, AGI renders inevitable.

AI’s smoke and mirrors moment

Because of course, AI is not inevitable. Not as a roundly successful product, and much less as a sentient, world-beating computer program. It may even be closer to the opposite: Report after report indicates that generative AI services are underperforming in the corporate world. The relentlessly hyped Humane AI Pin is a laughingstock. As I write this, the stock of Nvidia, whose chips undergird the AI boom, is tanking. OpenAI’s much-ballyhooed GPT store has so far come up short; developers and consumers alike find it inert and unimpressive. And that’s not even mentioning the copyright woes that plague the store and the industry at large.

So, AI company valuations are “coming down to earth,” as the Information put it, amid adjusted projections as to how much revenue the AI companies might actually be able to make. Some AI companies aren’t so much as “coming down” to earth, but crashing: Stability AI, once a frontrunner in AI image generation, saw an exodus of top staff as a litany of setbacks and scandals roiled the company, leading the embattled CEO, Emad Mostaque, to resign. Inflection, the high profile startup founded by Mustafa Suleyman, the former head of applied AI at Deepmind, was more or less poached piece by piece by Microsoft after struggling to gain market traction.

And yet. Sam Altman, who just debuted on the Forbes billionaire list, pushes ever onward, pronouncing visions of an AGI that will transform the world, seeking trillions of dollars in investment for chips and, most recently, $100 billion to build a supercomputer called Stargate with Microsoft.

It’s this story that propels the generative AI industrial complex onward, amid so many shortcomings and uncertainties. (That, and the multibillion dollar support from the tech giants and capital flows from the VC sector.) It’s the driving force behind why investors and corporate clients are still buying in — why, financial services firm Klarna, for one, says it has replaced the equivalent of 700 customer service workers with OpenAI products even when other companies’ recent attempts to do the same have backfired spectacularly. And why a large percentage of Fortune 500 companies are reportedly using generative AI. As a recent Times headline put it: “Will A.I. Boost Productivity? Companies Sure Hope So.”

All this is quite fortunate for Altman. And this is an element of the rise of AI that I don’t see discussed enough: His omnipotent AI is struggling to be born at an extremely convenient moment. There’s a tight labor market, high employment, and companies are very eager to embrace technological tools to either replace human workers or wield as leverage against them. Read through that Times piece, and you hear company after company hungry to slash labor costs with AI — if only they could! That’s the vision corporate America sees cast on the walls, the product of generative AI’s smoke and mirrors: Artificial systems that can save them lots of money by making workers disappear. Once it was the implied presence of the devil that underwrote the delusion that a charlatan could bring back the dead, today, it’s the specter of AGI that animates the idea that AI will finally unleash mass job automation.

Any threat to that show, however, is a threat to the generative AI enterprise at large. Last month, I wrote how the tide was turning for OpenAI: Between mounting legal woes and plateauing user growth, a disastrous Wall Street Journal interview and being booed at SXSW, the backlash, it seemed, had become at least as prominent as the mythos the world’s top AI company had worked so hard to generate for itself. And that’s a particularly pernicious problem for OpenAI and co; generative AI desperately needs that mythos. Once the narrative blows over, once the public, or at least the middle managers, get tired of waiting for real labor savings, aka more than analogical demonstrations of an incipient AGI — once the limits of the demonstration become too clear — the facade may begin to fall away from the entire phenomenon. In which case we’ll be left with text generators churning out reams of variously usable content, a pile of variously interesting chatbots, and automated JPEG producers that may or may not be infringing on copyright law thousands of times a day.

Unlike trends of the very recent past, generative AI has real gravitational pull — companies desperately do want the promised service to work here, unlike, say, the metaverse or web3 or crypto, when most companies had no idea what they were really supposed to do with the vaporous trend at hand. And there is real tech behind those smoke and mirrors. Even critics admit there are some good uses for generative AI — even if it’s not nearly good enough to justify the AI industry’s costs, harms, and messianic promises.

And so, with generative AI, we’re once again witnessing a core problem with entrusting technological development to a handful of self-mythologizing executives and founders in Silicon Valley. Instead of systems that are democratically and ethically constructed, built to serve humans and not just managers, whole constituencies and not just consultants; systems that could be very useful in some less-than earth-shattering ways, we get the smoke and mirrors. Again. And we can only hope that the magic lanterns of the 21st century haven’t cost us too much in the short term — in lost or damaged jobs, corrupted digital infrastructure, in the cheapening of culture — because by so many counts, that smoke is already beginning to waft away.

What might happen is what happened with the internet. What was hoped for (and touted incessantly) was a world in which everyone would have free access to good information (and even participation in decision making based on that). What we got was social media where we are not in the driving seat but where we are the product to be sold and the 'good' that comes from it — and there is 'good' — is the side effect. The question that becomes, what evil outcomes (follow the money is a good start) might we get? And will the net effect (for whatever that phrase means something here) be a positive one?

Note: I assume you know snake oil originally came from Chinese watersnakes and probably had some actual effect. If was *fake* snake oil that was the problem. There may be a usable analogy here too. GenAI will provide us with usable stuff, but it is peddled as a cure-all, like *fake* snake oil (from rattlesnakes) was.

"(Sometimes you stumble onto something so ripe with resonance you wish you could go back and add it retroactively to your book — would love to be able to add in a bit about phantasmagoria and magic lanterns to Blood in the Machine, but alas)."

And sometimes you stumble onto something that could be the seed of your next book?