The Critical AI Report, December 2024 Edition

Five important items for understanding the state of AI. READ THIS OR GET LEFT BEHIND.

Greetings all,

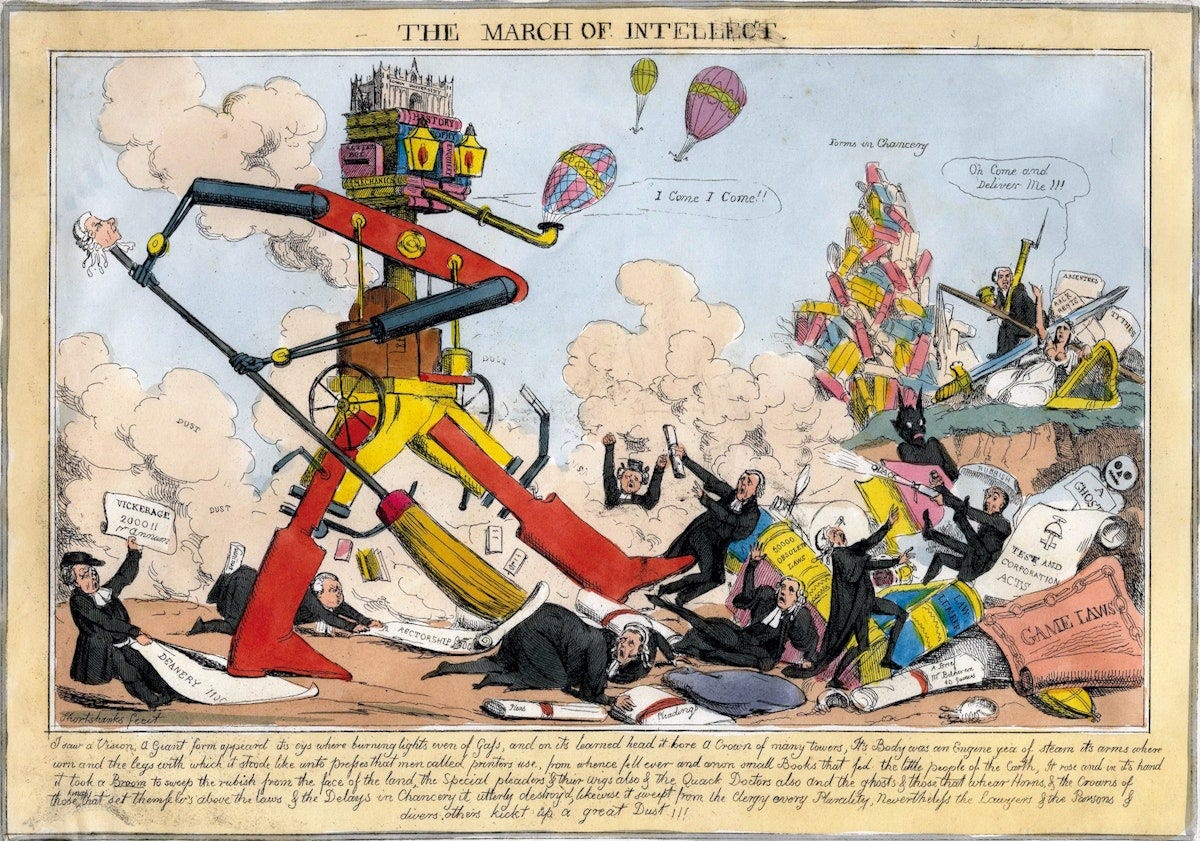

Welcome to the first installment of what I think I’ll be calling The Critical AI Report™®—a monthly (or bimonthly, you tell me how useful this is!) gathering of some of the best critical writing, news reports, papers, op-eds, and stray thoughts about AI in a given period. I’ll gather and dissect the writing that’s helping me make sense of our AI-saturated epoch, in the event that it might help you make sense of it too. I’ll try to add some historical and critical context, too.

There are plenty of roundups of AI press releases, business blogs, and corporate boosterism out there (AI WON’T TAKE YOUR JOB—SOMEONE USING AI WILL. READ THIS FOR 5 TIPS TO MASTER AI OR GET LEFT BEHIND etc etc), but fewer compilations I’ve come across of good, critical work on AI. In the future, this might be for paying subscribers—I certainly want to keep reporting and analysis open to all, but I if I am going to keep doing this newsletter, I’m probably going to have to find some way to MONETIZE it, as they say. Anyway, it’s a work in progress, so leave a comment below to let me know what you think, if this is a worthy undertaking, or what you’d like to see more of.

So without further ado, this month, we’ll dive into:

-Generative AI’s Real Impact on Workers

-How to Define ‘AI’ In the First Place

-Is Generative AI Corrupting the Information Ecosystem?

-The State of AI Content Production

-How Open Source AI Is Just as Closed

Plus: The True Origins of OpenAI, the AI emissions surge is expected to continue, the disingenuous AI critic debate, and Timnit Gebru asks, who’s tech really for?

As always, if you find this work valuable, subscribe away, and consider becoming a paid subscriber for the price of a cup of coffee a month—paid supporters make all of this possible, and many thanks if you’re already chipping in.

#1. Digging Into Generative AI’s Actual Impact on Workers So Far

One of the biggest question marks hanging over generative AI is what its impact on labor will ultimately be. Widespread job loss? Intermittent task automation? A new surveillance tool for managers? Tech companies are aggressively marketing enterprise software to corporations, with the explicit promise that AI will augment work, and the implicit promise that AI can slash labor costs. Results so far are mixed, but freelancers are losing clients and jobs are changing anyway.

Yet there have been few attempts to taxonomize how, exactly, AI is impacting the labor force writ large. (I spent a couple months investigating how AI was hitting the video game industry, but that’s just one field among hundreds that will be transfigured by AI.) So I was glad to see a new report, Generative AI and Labor: Power, Hype, and Value at Work, by Aiha Nguyen and Alexandra Mateescu at Data & Society, attempt exactly this.

The report examines the language used to sell generative AI to the working public, questions the foundations of the debate of whether AI will ‘augment’ or ‘replace’ workers, and looks at how the technology is materially entering workplaces—as well as at its propensity for creating additional ‘invisible’ tasks workers must complete to maintain an illusion of automation, adding layers of workplace surveillance, and clumsily commodifying work into data.

It helped me visualize and categorize the ways that generative AI is being used in workplaces and by companies, and—surprise!—shows that AI is most likely to prove disruptive, degrading, and concerning to workers when it is introduced by management as a specialized enterprise tool that the worker has little say or power over.

The report documents the amount of mostly unacknowledged labor that goes into both ensuring that generative AI can function as a commercial product in the first place—by labeling and ‘cleaning’ the data models are built upon, or providing quality assurance—and by correcting, editing, and sprucing up the output.

Since the dawn of automation, this has by and large been the name of the industrial game: A technology provides a manager, boss, or disruptor an opportunity to hire a less skilled worker, for cheaper, even if a comparable amount of labor is still required to create a similar product. Hence, the disruption.

From the report:

the output of generative AI often requires considerable reworking in order to appear to be labor-saving. Copywriters are hired to edit and “re-humanize” poorly written, AI-generated text while being paid less for doing similar work they had done in the past under the rationale that they contribute less value. Workers are expected to take on responsibilities assumed to be seamlessly delegated to AI. An industry-wide survey report from AP News examining journalists’ adoption of generative AI found that in some cases it functioned, as one journalist respondent put it, much like self-service checkout, in that staff journalists are increasingly expected to do extra editing or proofreading work that would have otherwise gone out to contract freelancers.

For all the hype about the transformative nature of AI, the primer makes clear that most transformations in the world of work will be dictated by managerial whims, and will take place within existing economic and corporate structures. The whole report is worth spending some time with.

#2. How to Define ‘AI’

The Data & Society report points out that nebulous definitions of AI help the tech companies wield whichever narratives about AI are most convenient for the market they’re seeking; furthermore, a good amount of gatekeeping goes on regarding what is and isn’t “AI”; a term that’s historically broad and pretty ambiguous. As such, a lot of people who aren’t engineers, AI researchers, or tech workers, but are interested in engaging with the technology’s broader social project, or its harms, are often made to feel uncomfortable or discouraged from defining the term the “wrong” way.

That’s not exactly where the computer scientist and anthropologist Ali Alkhatib begins his short piece “Defining AI,” but he winds up making some very important points on the front, the meat of which I’ll quote at length here:

I think we should shed the idea that AI is a technological artifact with political features and recognize it as a political artifact through and through. AI is an ideological project to shift authority and autonomy away from individuals, towards centralized structures of power. Projects that claim to “democratize” AI routinely conflate “democratization” with “commodification”. Even open-source AI projects often borrow from libertarian ideologies to help manufacture little fiefdoms.

This way of thinking about AI (as a political project that happens to be implemented technologically in myriad ways that are inconsequential to identifying the overarching project as “AI”) brings the discipline - reaching at least as far back as the 1950s and 60s, drenched in blood from military funding - into focus as part of the same continuous tradition.

Defining AI along political and ideological language allows us to think about things we experience and recognize productively as AI, without needing the self-serving supervision of computer scientists to allow or direct our collective work. We can recognize, based on our own knowledge and experience as people who deal with these systems, what’s part of this overarching project of disempowerment by the way that it renders autonomy farther away from us, by the way that it alienates our authority on the subjects of our own expertise.

Alkhatib ends the piece encouraging everyone to feel comfortable thinking through their own definitions accordingly—the better to engage with “AI” where it matters.

#3. How Generative AI is Impacting an Already Polluted Information Ecosystem

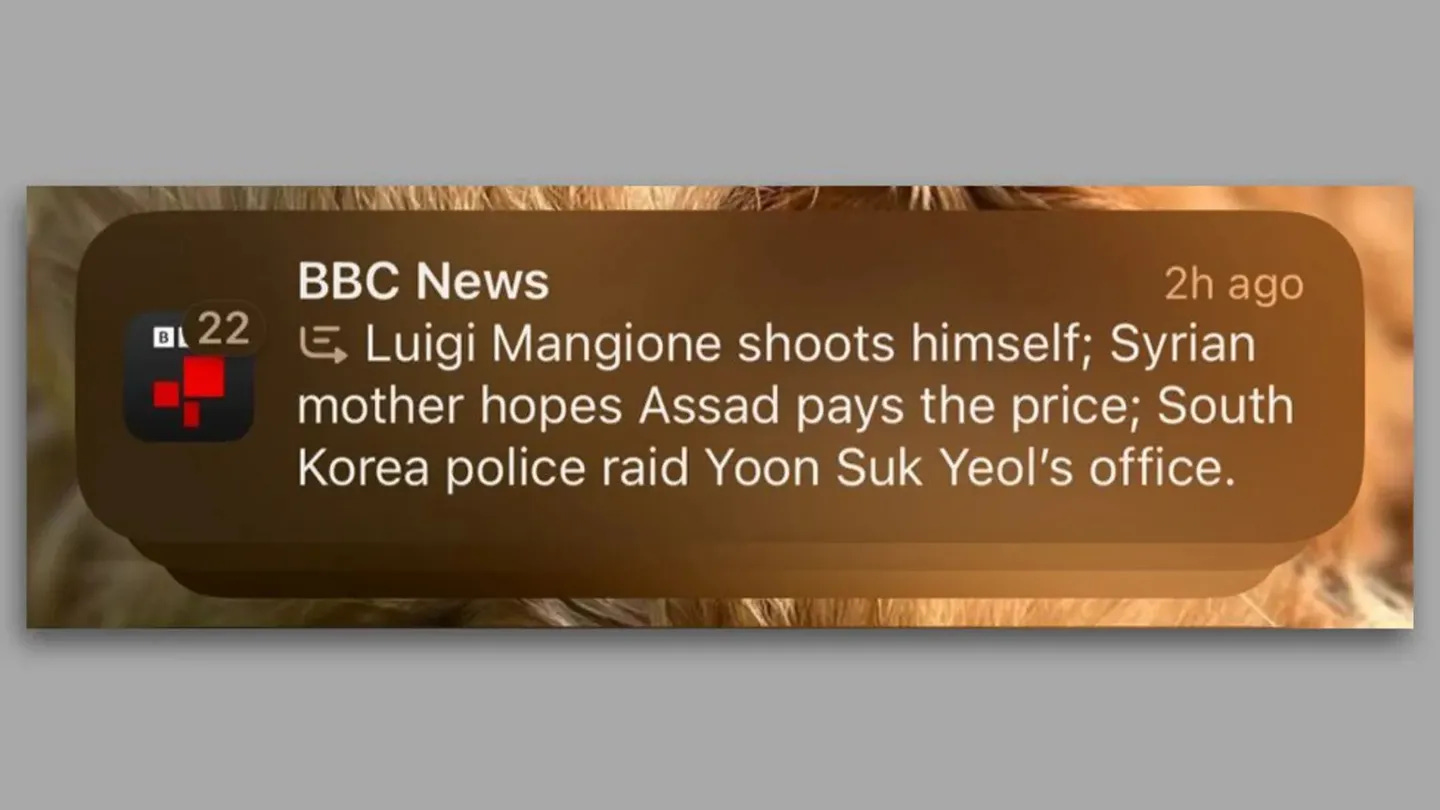

On December 13th, a number of iPhone users got a weird notification from the BBC. “Luigi Mangione shoots himself,” according to the venerable British news agency. Obviously, the alleged shooter of the United Healthcare CEO did no such thing; this was a complete fabrication concocted by Apple Intelligence, Apple’s newly launched generative AI feature.

From the BBC’s own report on the episode:

The BBC has complained to Apple after the tech giant's new iPhone feature generated a false headline about a high-profile murder in the United States.

Apple Intelligence, launched in the UK earlier this week, uses artificial intelligence (AI) to summarise and group together notifications.

This week, the AI-powered summary falsely made it appear BBC News had published an article claiming Luigi Mangione, the man arrested following the murder of healthcare insurance CEO Brian Thompson in New York, had shot himself. He has not.

A spokesperson from the BBC said the corporation had contacted Apple "to raise this concern and fix the problem".

Apple declined to comment.

What really raised my eyebrow here was that declination of comment—to me, it’s a sign of how much generative AI (and the last few years of general online enshittification) has moved the goalposts with regard to the expectation that our technical systems be, you know, reliable, or accurate. Apple Intelligence is getting things wrong left and right—big things, that, especially in a place like the UK, where defamation laws are stricter than the US, could land an org like the BBC in hot legal water—but so few lay users hold the tech to any standard of rigor that Apple has barely weighed in on it.

There was a time, not so long ago, when there would be a scandal over such a mistake—a tech company’s product made something up, attributed it to a respected news outlet, and sent it to millions of people—and Apple would at least see fit to issue a mea culpa. Today, it’s just written off as another case of AI making shit up. This is not great.

Teachers are already documenting their struggles with more and more students taking the output of AI programs as gospel, or using it as a shortcut to demonstrating knowledge. Levels of public trust in news outlets are already rock bottom. Social media networks are gutting content moderation. The information ecosystem is already perilously polluted. And now we have unreliable text automation software in use on the biggest stages, with few repercussions if anything goes wrong.

Perhaps the very biggest stage on which generative AI is deployed is Google’s AI Overview. By some counts, Google processes 8 billion search queries a day; many of those searches are now greeted with an AI Overview for an answer, first thing. Mashable’s Mike Pearl undertook an investigation to try to determine the state of the AI service now that it had been rolled out for 6 months. What he found will surprise few, I suspect—the answers are still sometimes wrong in strange and demonstrable ways, the Overview is confident in its wrongness, and the system is ill-equipped to flag false responses:

It would be hard to argue point-blank that there's been a significant uptick in quality. Overviews materialize less often, and errors are still rampant, but I did find some very limited evidence of improvements: the AI Overviews for the queries I highlighted to Google for this article all improved while I was working on it.

The capacity for Google Overview to provide meme-worthy bad information has been dulled with time and crisis PR interventions, it seems, but the technology underpinning the whole affair hasn’t dramatically or demonstrably improved. Instead, people are getting fed less sensational bits of dubious information, and disincentivized from clicking links to actual sources. As Pearl points out, it’s not like Google was a bastion of irrefutable truth before generative AI took over, but I think the continued erosion is palpable. And it’s only slated to continue to spread.

#4. The AI-Generated Culture is Here

One additional place AI-generated content is spreading, apparently, is to TV channels. 404 Media’s Jason Koebler documented his trip to the hallowed Chinese Theater in Los Angeles to watch a spate of AI-generated films targeted advertising intended to round out offerings on a TV manufacturer’s default streaming channels:

I’m sitting in the Chinese Theater watching AI-generated movies in which the directors sometimes cannot make the characters consistently look the same, or make audio sync with lips in a natural-seeming way, and I am thinking about the emotions these films are giving me. The emotion that I feel most strongly is “guilt,” because I know there is no way to write about what I am watching without explaining that these are bad films, and I cannot believe that they are going to be imminently commercially released, and the people who made them are all sitting around me.

Then I remembered that I am not watching student films made with love by an enthusiastic high school student. I am watching films that were made for TCL, the largest TV manufacturer on Earth as part of a pilot program designed to normalize AI movies and TV shows for an audience that it plans to monetize explicitly with targeted advertising and whose internal data suggests that the people who watch its free television streaming network are too lazy to change the channel. I know this is the plan because TCL’s executives just told the audience that this is the plan.

TCL said it expects to sell 43 million televisions this year. To augment the revenue from its TV sales, it has created a free TV service called TCL+, which is supported by targeted advertising. A few months ago, TCL announced the creation of the TCL Film Machine, which is a studio that is creating AI-generated films that will run on TCL+. TCL invited me to the TCL Chinese Theater, which it now owns, to watch the first five AI-generated films that will air on TCL+ starting this week.

Before airing the short, AI-generated films, Haohong Wang, the general manager of TCL Research America, gave a presentation in which he explained that TCL’s AI movie and TV strategy would be informed and funded by targeted advertising, and that its content will “create a flywheel effect funded by two forces, advertising and AI.” He then pulled up a slide that suggested AI-generated “free premium originals” would be a “new era” of filmmaking alongside the Silent Film era, the Golden Age of Hollywood, etc.

To TCL’s credit, this absolutely feels like the appropriate horizon for AI-generated films right now—100%, no-holds barred, crass commercialization of content with no pretenses to actual art, aimed at a very specific audience: People who are simply too lazy to see if literally anything else is on TV right now.

Which brings us to perhaps the best polemic against generative AI I ran across this month so far; Kelsey McKinney, the host of the hit podcast Normal Gossip and the author of a forthcoming book, also about Gossip, wrote an essay in Defector inspired by the same industry-infuriating book automators I mentioned a couple weeks ago. The whole thing is worth reading, but I especially enjoyed the bit that gets at how companies like this are primed to pitch AI and automation of struggling creative industries because they’ve been squeezed by corporate cost cutting and downsizing for years already:

the delays in the publishing system are not because humans are slow and humans make mistakes. It is because the people who are in charge of these massive corporations have reduced the size of their workforce so that now their employees are doing the jobs of multiple people. The leaders of these companies decided at some point that speed was less of a priority than saving money, and now they are trying to have it both ways. HarperCollins is asking authors to opt-in to letting AI train itself on their books. In recent interview with Publisher's Weekly, the CEO of HarperCollins riffed on the vague idea of "a 'talking book,' where a book sits atop a large language model, allowing readers to converse with an AI facsimile of its author." The same article mentioned that HarperCollins is more profitable because of layoffs this year.

#5. Closing Up Open-Source AI

Finally, to round things out, there was a great paper in the journal Nature, by David Gray Widder, Meredith Whittaker, and Sarah Myers West, arguing that the open source vs closed source debate in AI is creating something of a false binary—the open source approach is unlikely, in its current configuration, to do much to prevent the companies deploying it from concentrating power or to protect users’ data.

The paper’s title sums it up pretty well: Why ‘open’ AI systems are actually closed, and why this matters. From the abstract:

At present, powerful actors are seeking to shape policy using claims that ‘open’ AI is either beneficial to innovation and democracy, on the one hand, or detrimental to safety, on the other. When policy is being shaped, definitions matter. To add clarity to this debate, we examine the basis for claims of openness in AI, and offer a material analysis of what AI is and what ‘openness’ in AI can and cannot provide: examining models, data, labour, frameworks, and computational power. We highlight three main affordances of ‘open’ AI, namely transparency, reusability, and extensibility, and we observe that maximally ‘open’ AI allows some forms of oversight and experimentation on top of existing models. However, we find that openness alone does not perturb the concentration of power in AI. Just as many traditional open-source software projects were co-opted in various ways by large technology companies, we show how rhetoric around ‘open’ AI is frequently wielded in ways that exacerbate rather than reduce concentration of power in the AI sector.

The biggest and most famous proponent of ‘open’ approaches to AI is Meta, whose LLaMa is a competitor to OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google’s AI products. I’ve long thought that its noisy embrace of an ‘open’ approach can be seen much less of a philosophical position, and more of a tactic to attempt to hamstring Meta’s more successful AI competition. This report cuts to the core of how hollow a lot of Meta’s rhetoric really is, which is not to say that ‘open source’ on its own is an ignoble pursuit, far from it, but that the framework can be and has been cynically deployed by corporate actors.

As the paper concludes:

Unless pursued alongside other strong measures to address the concentration of power in AI, including antitrust enforcement and data privacy protections, the pursuit of openness on its own will be unlikely to yield much benefit. This is because the terms of transparency, and the infrastructures required for reuse and extension, will continue to be set by these same powerful companies, who will be unlikely to consent to meaningful checks that conflict with their profit and growth incentives.

The Critical AI Link Depot of Must Reads

-Who is Tech Really For? Timnit Gebru, the New York Times

-AI’s emissions are about to skyrocket even further. James O’Donnell, MIT Technology Review. And Generative AI and Climate Change Are on a Collision Course, Sasha Luccioni, WIRED, and AI is Guzzling Gas, Arielle Samuelson, HEATED.

-Platformer’s Casey Newton set off a round or three of heated AI critical discourse when he divided AI coverage into two camps, that written by those who believe AI is “real and dangerous” and that written by those who think it’s “fake and dumb,” singling out Gary Marcus, but implicitly taking aim at folks like Ed Zitron and myself. I debated weighing in, but Ed Ongweso Jr. went ahead and made most of the points I would have made, albeit more, uh, vociferously, than I would have, in his great and fiery response. “AI can be real and fake and suck and dangerous all at the same time or in different configurations,” as he writes, which pretty much sums it up.

But for those who want to follow along at home, here’s the timeline:

-The phony comforts of AI skepticism, by Casey Newton, Platformer.

-Hard-forked! Casey Newton’s distorted portrait of Gary Marcus and AI skepticism, by Gary Marcus, Marcus on AI.

-The phony comforts of useful idiots, by Ed Ongweso Jr, the Tech Bubble

-Weighing in on Casey Newton's "AI is fake and sucks" debate, by David Karpf, the Future Now and Then

-Dismissing critics has “real and dangerous” consequences, by Paris Marx, Disconnect

-Godot Isn’t Making It, by Ed Zitron, Where’s Your Ed At. (Ed didn’t weigh in directly on the debate, but this is a good piece on AI hype, and part of what Casey was trying to criticize in his broadside, for context.)

I think that’s the best stuff to read here: Casey responded in a paywalled post, and Marcus responded to that, but that’s pretty much the lay of the land.

If I’m rounding up stray critical AI links here, I’d be remiss not to mention my own report, AI Generated Business, published last month by the AI Now Institute. Check it out if you haven’t yet, curious to hear folks’ thoughts.

Okay, that’s it for the very first edition of the Critical AI Report. Please share thoughts and ideas and send stories, artifacts, and ideas for future installments in the comments below, or drop a line by email. Look forward to hearing from everyone, hammers up, and happy holidays.

Glad I'll be left behind when it comes to AI TV. I think many assume that AI is for the collective good, when in reality they forget the military industrial application, or don't want to discuss for fear of being labeled "backward" or worse yet - a conspiracy theorist.

This is why Musk often gets a pass, and is allowed to irradiate our planet with satellites, not to mention the drones that function on AI Killware like Lattice from Anduril.

Most excellent report! Thanks😊