Four bad AI futures take root

A whole week of d-list Black Mirror episodes come true

Over the past week or so, there’s been little need to imagine dystopian visions of what a world overrun by some of the worst-case AI scenarios might look like—the tech industry and its acolytes happily offered them up to us. And while grim portents of AI’s impacts on society and culture are not exactly uncommon, it’s somewhat rare we get to experience the full gamut of bad AI futures in such a compressed timeframe.

Or at least it felt that way to me, and I tend to watch these things pretty closely—that’s the job. From stark evidence that AI is undermining a generation of students’ ability to learn in higher ed, to tech companies vowing to replace workers with AI, to a victim’s family using an AI avatar of the deceased to sway the courts, this was one of those stretches where I swear I could feel the brunt force of an unwelcome future arriving at speed, in stagger-step. That some of the unhappiest impacts of AI—the product of an industry-wide push to thrust AI products into every plane of existence—are no longer speculative, but manifesting, taking shape, and entrenching.

As Harvard historian Erik Baker put it in response to one of the above stories, “Beginning to feel consumed by what I can only describe as climate anxiety but for AI.” I’m pretty numb to it by now, but even I felt that this week, too—it’s hard for any good humanist not to. There were at least four distinct bad AI futures articulated by Silicon Valley and co., by my count. So let’s break them down, one by one.

Before we do; Blood in the Machine is a 100% reader-supported publication, made possible by subscribers who kick in a few bucks a month to back this work. To do the same, and to help support my journalism, sign up to be a free or paid subscriber. Many thanks, and hammers up.

Bad AI Future of the Week #1: 80% of your friends are AI-generated

First, let’s pay a visit to our friend Mark Zuckerberg, who is making the press rounds touting Meta’s AI plans. The CEO proclaimed that he the average American only has three friends, but wants fifteen, and that AI-generated avatars can make up the difference.

Here’s the Wall Street Journal, reporting on Zuck’s media blitz:

“The average American I think has, it’s fewer than three friends, three people they’d consider friends, and the average person has demand for meaningfully more, I think it’s like 15 friends,” he said in the interview with podcaster Dwarkesh Patel.

On a separate podcast with media analyst Ben Thompson, Zuckerberg continued: “For people who don’t have a person who’s a therapist, I think everyone will have an AI.”

…

The Meta CEO is now throwing resources at AI chatbots—both in its social media apps and in its hardware devices. Meta AI, as it is called, is accessible via Instagram and Facebook, as a stand-alone app and on Meta’s Ray-Ban smart glasses. Zuckerberg said Tuesday that nearly a billion people are using the feature now monthly.

Zuckerberg said personalized AI isn’t just about knowing basic information about a user, it’s about ensuring chatbots behave as a good friend might.

“You have a deep understanding of what’s going on in this person’s life,” he said.

Set aside for a second how deeply pathetic this imagined future is, and what it says about the man advocating for it, and consider that this is what Meta is actively trying to build. A digital ecosystem designed to maximize users’ time on platform, populated by AI-generated “friends” spun out of the data a user has fed that platform over time about his life and preferences.

Closer to the opposite of helping folks find actual companionship, it’s a recipe for more isolation and loneliness—which is exactly the point, as my good friend Paris Marx points out in his newsletter, since the goal is to get these AI friends to help Zuck sell more targeted advertising.

There is, without a doubt, a loneliness epidemic afflicting millions. And I do not blame anyone that may find relief from it in an AI chatbot—but let’s be clear that tech companies like Meta, with its array of addictive and youth-targeting social media networks, created the very conditions that gave rise to said epidemic. It built and sold this very future, of online connection over all else! Meta now hopes to sell a solution to the modern friendship problem via more personalized digital products that, surprise, further exacerbate the loneliness plague while staking out new revenue streams for the company.

And just think for a second about what this future actually looks and feels like, position yourself in front of your monitor, or on your phone late at night, in a Facebook Messenger group chat with, oh, eight of your fifteen AI friends, a medley of auto-generated texts filling the screen, reversions to the mean of human banter, human gossip, human flirting, ignoring the ads, and intuiting on some level that everything being said has been said before, by a person. This is the frontrunner for the future of AI-infused social media, and it is bleak.

Bad AI Future of the Week #2: College is where you go to learn how to use ChatGPT to cheat

The truly viral AI story of the week was the New York Mag piece, “Everyone Is Cheating Their Way Through College,” by James D. Walsh, whose subhed argues that “ChatGPT has unraveled the entire academic project.” The story treads ground that has certainly been trod before, but in nabbing some truly excellent and chilling quotes from students who are now so inured to using ChatGPT to cheat that they apparently do not hesitate to talk to reporters about it, it ups the moral panic quotient by a good order of magnitude or two.

And don’t get me wrong, some of that moral panic is well-deserved. Here’s how the piece begins:

Chungin “Roy” Lee stepped onto Columbia University’s campus this past fall and, by his own admission, proceeded to use generative artificial intelligence to cheat on nearly every assignment. As a computer-science major, he depended on AI for his introductory programming classes: “I’d just dump the prompt into ChatGPT and hand in whatever it spat out.” By his rough math, AI wrote 80 percent of every essay he turned in. “At the end, I’d put on the finishing touches. I’d just insert 20 percent of my humanity, my voice, into it,” Lee told me recently.

Lee was born in South Korea and grew up outside Atlanta, where his parents run a college-prep consulting business... When he started at Columbia as a sophomore this past September, he didn’t worry much about academics or his GPA. “Most assignments in college are not relevant,” he told me. “They’re hackable by AI, and I just had no interest in doing them.” While other new students fretted over the university’s rigorous core curriculum, described by the school as “intellectually expansive” and “personally transformative,” Lee used AI to breeze through with minimal effort. When I asked him why he had gone through so much trouble to get to an Ivy League university only to off-load all of the learning to a robot, he said, “It’s the best place to meet your co-founder and your wife.”

The story paints a portrait of the modern student as not just willing to use ChatGPT for just about any assignment, but reliant on it to do so. Along with that last bit about the student going to college primarily to meet his partner and co-founder, the other quote that got passed around most was from a professor at Chico State:

“Massive numbers of students are going to emerge from university with degrees, and into the workforce, who are essentially illiterate,” he said. “Both in the literal sense and in the sense of being historically illiterate and having no knowledge of their own culture, much less anyone else’s.”

Combined, they provide the grist for this bad future mill: The institution of higher education, which we hold as crucial for developing critical thinking skills and a broad understanding of history, science, and society, is being transmuted into a place students attend largely for the sake of status, to be navigated largely by the automating of degree obtainment.

Clearly, a large part of college has always been about status, and kids have always found ways to cheat or get around homework, but there’s something new and unnerving here. My partner is a college professor, and I have heard a lot of similar stories already—attention spans are shot, kids don’t want to come to class, and ChatGPT use really is rampant. The result seems to be that there truly are fewer students inclined to put in the manual mental labor to do good, original classwork, and we risk seeing what you might describe as a collective crisis in critical thought.

This, of course, would delight the AI companies, which have purposefully targeted students as a market demographic. During finals season, OpenAI offered its premium chatbot tier to students for free. Demonstrating that ChatGPT can successfully help them automate doing homework and cheat on tests underlines the tools’ utility and ingratiates the product to its young users, who, as the piece describes, become reliant on the app for everything else, too.

It’s also what makes Lee such a perfect subject for the story—he both uses ChatGPT to cheat at Columbia, and admits he is only there to acquire the social capital and network necessary to build a tech startup that will further export that cheating around the world. He’s an avatar for Silicon Valley and the AI boom’s ethos writ large. College for him has been reduced to some buttons to press to better prepare for his startup’s chance at success.

Now fast forward and take this trend to its logical conclusion, too—teachers and professors have slackened standards to meet the new reality that everyone uses AI apps, 80%1 of all homework and mental labor is carried out with automation software, and the next generation becomes reliant on a few Silicon Valley companies to provide it with knowledge and answers. Those among the upper middle class that can still afford to go to college takes one step closer to becoming the Eloi.

Bad AI Future of the Week #3: AI-generated fantasies are now admissible in court

One thing that might happen if your critical thinking skills have eroded is that you might watch an AI-generated video in which a recreation of a man who has died issues a message from the grave, and believe that it had any bearing on reality. Alas, this is exactly what a judge in Arizona did.

Here’s the background, courtesy of 404 Media:

An AI avatar made to look and sound like the likeness of a man who was killed in a road rage incident addressed the court and the man who killed him: “To Gabriel Horcasitas, the man who shot me, it is a shame we encountered each other that day in those circumstances,” the AI avatar of Christopher Pelkey said. “In another life we probably could have been friends. I believe in forgiveness and a God who forgives. I still do.”

It was the first time the AI avatar of a victim—in this case, a dead man—has ever addressed a court, and it raises many questions about the use of this type of technology in future court proceedings.

The avatar was made by Pelkey’s sister, Stacey Wales.

Wales and her brother both work in tech, and they made the video together. It was submitted as the victim’s own impact statement during a sentencing hearing, the first time that such a thing has happened, and the judge was so moved by the AI that he handed down a sentence one year longer than the prosecution had asked for.

“I loved that AI, and thank you for that,” the judge said. Fittingly, perhaps, Stacey Wales told 404 that she struggled with writing her own impact statement for months before deciding to outsource it to AI.

This future is bad particularly in light of the past two—we’ve got compounding bad futures here—because we’re staring into the maw of a world where we are outsourcing our critical faculties to AI, spending more time in isolation in spaces mediated by still more AI, and now, stuff like fantastical AI-generated victim statements can sway criminal sentencing, and, presumably, much more.

Bad AI Future of the Week #4: “AI is coming for you”

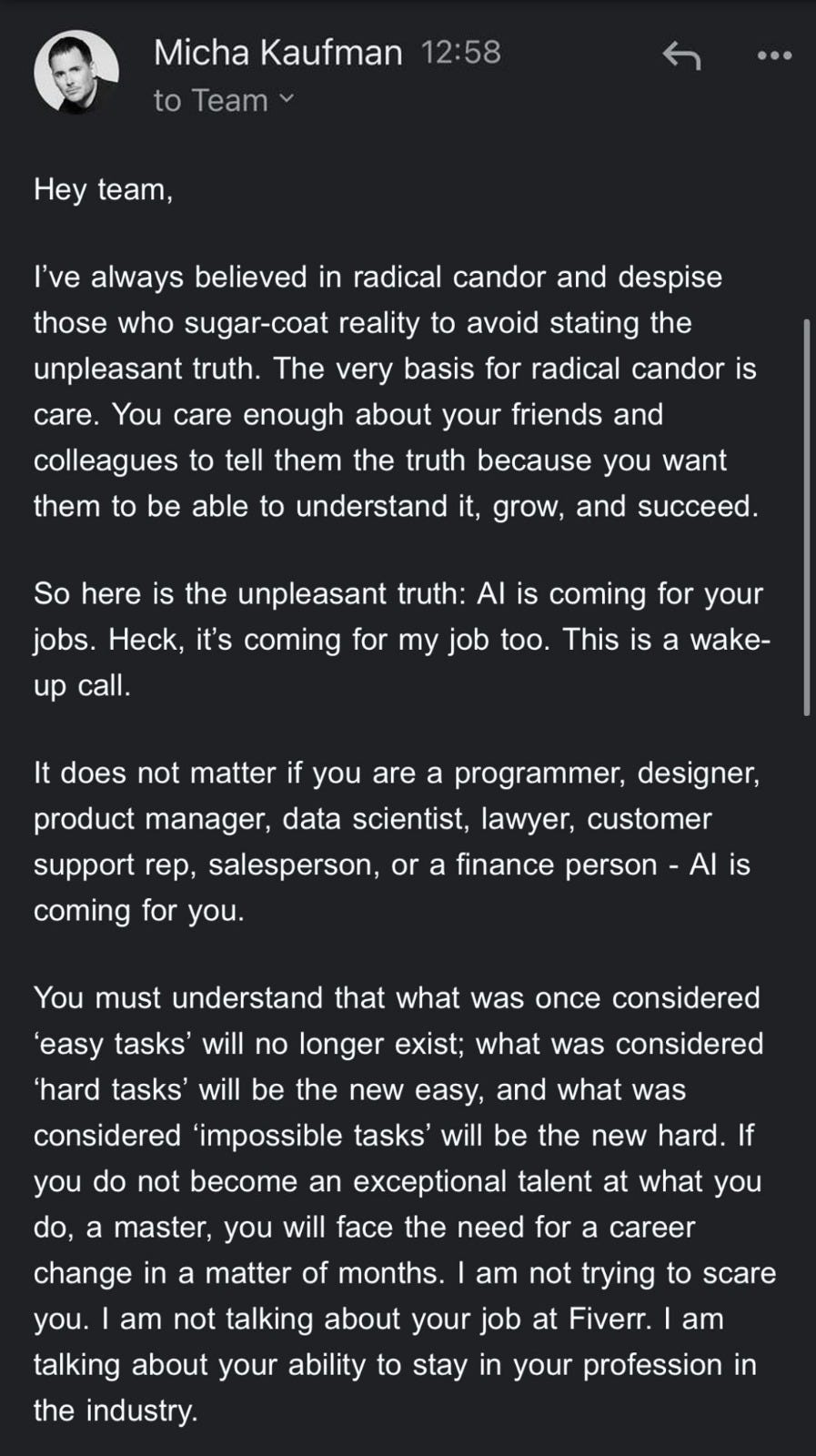

You’ve probably heard a good deal about this one at this point, especially if you read this newsletter, so I’ll keep it brief—last week, I broke news that Duolingo has fired scores of its human writers and translators and replaced them with AI systems. This week, the CEO of the gig work app Fiverr heaped some fuel on the fire, telling his company that AI was coming for all of their jobs.

In this vision, more aggressive than the sort promised by Sam Altman and most of the big tech companies, which always temper their prognostications of world-changing disruption with some mention of abundance or flourishing. Not Kaufman, who himself helms a tech company all but premised on worker exploitation (Fiverr connects users to freelance gig workers for tasks and odd jobs, with the historic starting rate of $5 per job), who prefers his sentient AI to take on a more malevolent air.

Now, it’s important to understand that “AI” is not “coming for you” or your jobs—much as he might protest the supposition, people like Micha Kaufman are coming for your jobs. Executives and managers like him are choosing to use AI to deskill, surveil, and to try to replace workers, and framing it all in the trappings of inevitability.

I’ve just started a project—AI Killed My Job2—that seeks to explore this very phenomenon, which is rampant in certain industries like translation and illustration. I’ve already heard from nearly 50 workers who’ve had their jobs impacted by bosses and managers using AI, and thus far a common theme is that the AI is often used to replace work *even when it’s not very good*. It’s the logic and promise of AI that is so powerful to managers, not always the product.

AI chatbots and companions are already proving addictive—and sometimes deadly—to youth who use them too much. A group of researchers at Stanford and Common Sense Media determined, unequivocally, that kids should avoid AI companions under force of law. But Silicon Valley is aiming their AI products at the youth demographic nonetheless, bent on selling its homework machines to college and high school students. Into this environment, we’re seeing a collapse of rigor in considering AI outputs, which is bending reality towards automated fantasia in disconcerting ways. All of which prepares the substrate of humanity that shuffles out of AI-mediated social networks and automated colleges for a job inputting commands into an AI content generator of one kind or another. If this sounds bleak, well, these are the tech industry’s visions, not mine! This is the state of play, where Silicon Valley is concentrating its efforts, and where AI stands to inflict some of its most serious harms—on young people’s social lives, on education and critical thought, on our shared sense of reality, and on our ability to find and do meaningful work.

But! It’s also crucial to note that those nascent futures are very much contestable, and while they are entrenching, they are not yet by any means determined. Do not lose heart, or hope, in other words, as AI anxious as you may be. It will almost certainly take mass organizing and political action to limit and unwind some of this damage—if the AI bubble does not burst of its own accord, and probably even if it does—but AI is no genie, and it’s only out of the bottle, unfettered, if we allow it to be.

That’s it for this week. I’ll check in next week with a State of the Blog, and more. Until then, a couple notes:

Paris Marx and I cover some of the above topics and more in this week’s System Crash, which also zooms in on OpenAI’s failed effort to restructure as a for-profit company. Give it a listen here.

The response to AI Killed My Job has been incredible so far. So many great and harrowing and sad and even funny stories about management, bosses, and competitors using AI to take or kill jobs. Please keep the submissions coming, and share with your networks, and share your story at AIKilledMyJob@pm.me.

A figure cited in the NY Mag piece.

I realize I am perhaps contributing to the semantic confusion here with this title but I also wanted it to encompass cases where AI killed what was fun about the job, and preference the brevity over specificity. I may come to regret this.

After watching that posthumous AI statement, I had to drop my phone to say WHAT. THE. FUCK. The video itself was creepy as hell. But not 10% as creepy as a judge - a judge!!! - knowingly changing a sentence because of it. Dear Lord.

I feel like we need to have a family meeting, but for all of civilization, over that college cheating piece. Here is the NYMag article, unpaywalled https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/technology/everyone-is-cheating-their-way-through-college/ar-AA1EjCRk .