For tech CEOs, the dystopia is the point

We mock Musk, Altman and Zuck for using bleak sci-fi references to market products — but these 'useful dystopias' might just be the point

Hello, and welcome back to Blood in the Machine: The Newsletter. (As opposed to, say, Blood in the Machine: The Book.) It’s a one-man publication that covers big tech, labor, and AI. It’s free, though if you’d like to back my independent tech journalism and criticism, I’d be thrilled if you’d consider pledging support. But enough about all that; grab your hammers, onwards, and thanks for reading.

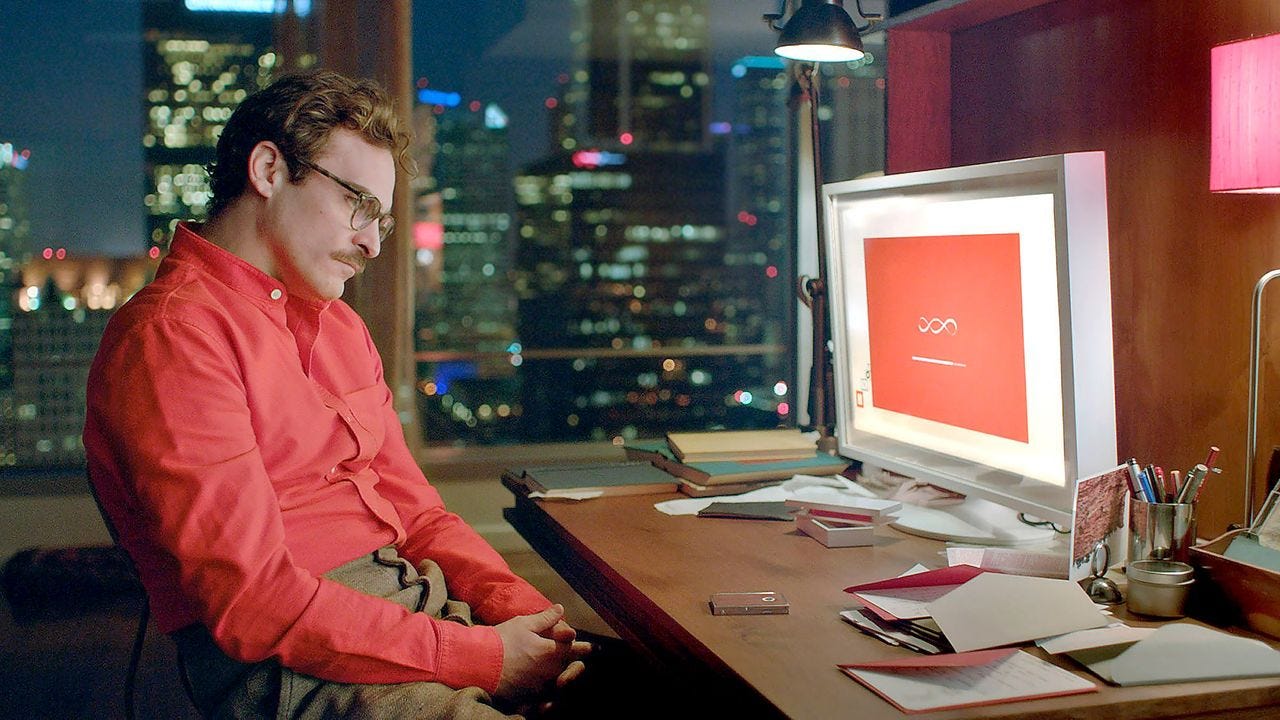

When OpenAI debuted its new voice interface program, ChatGPT-4o, it quickly invited a flood of comparisons to Her, the 2013 Spike Jones film in which Joaquin Phoenix falls in love with a program voiced by Scarlett Johansson. The comparison was encouraged by OpenAI — both in the very design of the flirty voice agent itself, which sounds suspiciously like Johansson, and by CEO Sam Altman himself, who tweeted “her” as the demo was underway.

In response, observers — myself included — took to what’s become a time-honored internet tradition: pointing out that the science fictional reference point a tech founder put forward was not an aspirational one, but, in fact, a dystopia containing a warning meant to be heeded, not emulated.

“I Am Once Again Asking Our Tech Overlords to Watch the Whole Movie,” Wired’s Brian Barrett wrote in a fun piece that runs through recent some recent offenders in the genre, including Elon Musk and his suggestion that the Cybertruck is “what bladerunner [sic] would have driven,” and Mark Zuckerberg’s love of the metaverse, the idea for which came from Snowcrash and Ready Player One — both pessimistic cyberpunk dystopias.

“Begging the AI companies building stuff modeled on "Her" to finish the movie!” the New York Times’ Kevin Roose wrote on X. “It does not end well!”

That tech executives have a penchant for mining inspiration from dystopian sci-fi films and books has become a running gag at this point — I wrote a longish piece for Motherboard (RIP) needling Zuck for trying to cash in on a dystopian metaverse back in 2021 — but maybe best nailed by the infamous Torment Nexus tweet:

That’s the gist of it! And yet. As much as we needle, or mock, or point out that the tech titans are stripping their references and products of context — it’s all in vain. The CEOs obviously don’t much care what some flyby cultural critics think of their branding aspirations, but beyond even that, we have to bear in mind that these dystopias are actively useful to them.

What’s the common denominator of Elon Musk’s cybertruck Blade Runner pitch/dystopia and Mark Zuckerberg’s metaverse pitch/dystopia? That the presumed user or owner of the product is the protagonist! If you buy a cybertruck, you’ll keep yourself safe from a world on the brink, from replicants, whatever. If you’re in the metaverse, you can be like the guy from Ready Player One; a hero going on all kinds of adventures even if the world at large is collapsing outside the VR helmet — it’s a useful dystopia for marketing what is otherwise an antisocial and cumbersome technology.

With Her, it’s even simpler — lots of people, especially lonely men, would like to be surrounded full-time by a Scarlett Johansson bot that acts like it cares deeply about them and thinks they’re funny. Who cares if ultimately it is revealed in the film that the AI was not actually engaging in a personal loving relationship with the protagonist but a simulation of one, and that simulation was keeping him — and humans everywhere — from enjoying basic human experiences and depriving them of lasting connection with other people? It’s a personal 24/7 Scarlett Johansson AI companion.

So it turns out it is aspirational branding, it’s just a deeply misanthropic variety — we want you to have the cool high tech thing, even if it is at the expense of everyone else, or the wellbeing of, well, society in general. And that happens to track pretty well with the ideology of the founders making these sci fi-referencing products in the first place.

Elon Musk, after all, disdains unions and public transit, his greatest hope is to leave earth for Mars, and he’s become a full-blooded anti-immigration reactionary on X. His useful dystopia is a world that’s part Blade Runner, part Mad Max (his actual grasp of the film, uh, doesn’t seem to be all that great; it appears to scan to him as a futuristic apocalypse where the cop who hunts robots is the guy you root for), and he uses it to sell products like the Cybertruck, which consumers might use to survive it. Same can be said of his other prominent products — with Tesla, Musk has begun shying away from pitching it as a solution to climate change, and leaning into pitching it as a self-driving pleasure capsule, with big screens and high top speeds. (The better to zip through, and ignore, a crumbling world.)

Mark Zuckerberg, meanwhile, is a man who bought up the four closest homes in his neighborhood and had them demolished so he would have more space to himself; fitting, then, that his metaverse is an intensely isolated digital experience whose aim is to close out the physical world. For his own personal purposes, the metaverse framework is a useful dystopia for advocating precisely this end.

Finally, Sam Altman, who is an end times prepper with a patch of land in Big Sur he plans on flying to if the going gets tough, may indeed be worried about the existential risk posed by AGI. Yet he seems rather unconcerned with the social risks much more likely to materialize in the short term. As such, it’s hard to think of a more useful dystopia than the one that promises to connect your users to a virtual, always-available ScarJo simulacrum.

It’s also a way to grab some easy cultural currency, and play into the ambient anxieties the public has around a consumer technology that, in reality, probably isn’t quite as advanced as he’d like them to think. (Another possibility is that Altman’s film interpretation skills may simply be lacking; this is the man who famously tweeted, “i was hoping that the oppenheimer movie would inspire a generation of kids to be physicists but it really missed the mark on that… i think the social network managed to do this for startup founders.” He may have fully assumed that Her is a two-hour advertisement for hot-sounding AI assistants.)

By attaching the new product to a popular speculation, especially one with built-in dramatic tension, the founders can elevate a buggy, unproven, or partially conceived technology into the cultural firmament, even if only briefly. It’s a cheat code, a way of getting us to relate to a future that’s already been culturally prototyped, and it can be quite successful. To wit: The day after admonishing tech companies for using Her as a benchmark for their products, Roose dedicated his column to explaining how AI’s ‘Her’ Era Has Arrived — thus further entrenching the link between OpenAI’s aspirational technology and its attendant useful dystopia in the public consciousness. Hell, my own story about the grim origins of the metaverse probably made Facebook’s deeply lame Horizons VR product seem orders of magnitude cooler than it turned out to be.

Even if consumers aren’t aware of all of the dystopian reference points these founders and companies are pushing, they probably should be aware of the narcissistic, us-against-the-collapsing-world mentality that is active behind them. And we shouldn’t merely mock the tech set for using dystopias as marketing materials — we should try to stop them from creating them, too.

Time for a Butlerian Jihad.

Who says that Her is an *inspiration* for Open AI? I am wondering, is all.

It is a reference point. A story many people are familiar. A shortcut for describing the type of voice interaction with an AI that is being approached.

Or, the other way around: watching the demo reminds people who are familiar with the movie Her of that film.

It is an interesting topic to explore how relationships with AI will develop, and what the implications are. Humans care about specific animals, their pets. They usually don’t extend the same care to the entire species. Humans have a tendency to be personal, and they will also have that when interacting with AI.