AI disagreements

Inside a closed-door AI doomer conference with rationalists, tech executives, and the acolytes of Silicon Valley's "new religion"

Hello all,

Well, here’s to another relentless week of (mostly bad) AI news. Between the AI bubble discourse—my contribution, a short blog on the implications of an economy propped up by AI, is doing numbers, as they say—and the AI-generated mass shooting victim discourse, I’ve barely had time to get into OpenAI. The ballooning startup has released its highly anticipated GPT-5 model, as well as its first actually “open” model in years, and is considering a share sale that would value it at $500 billion. And then there’s the New York Times’ whole package of stories on Silicon Valley’s new AI-fueled ‘Hard Tech’ era.

That package includes a Mike Isaac piece on the vibe shift in the Bay Area, from the playful-presenting vibes of the Googles and Facebooks of yesteryear, to the survival-of-the-fittest, increasingly right-wing-coded vibes of the AI era, and a Kate Conger report on what that shift has meant for tech workers. A third, by Cade Metz, about “the Rise of Silicon Valley’s Techno-Religion,” was focused largely on the rationalist, effective altruist, and AI doomer movement rising in the Bay, and whose base is a compound in Berkeley called Lighthaven. The piece’s money quote is from Greg M. Epstein, a Harvard chaplain and author of a book about the rise of tech as a new religion. “What do cultish and fundamentalist religions often do?” he said. “They get people to ignore their common sense about problems in the here and now in order to focus their attention on some fantastical future.”

All this reminded me that not only had I been to the apparently secret grounds of Lighthaven (the Times was denied entry), late last year, where I was invited to attend a closed door meeting of AI researchers, rationalists, doomers, and accelerationists, but I had written an account of the whole affair and left it unpublished. It was during the holidays, I’d never satisfactorily polished the piece, and I wasn’t doing the newsletter regularly yet, so I just kind of forgot about it. I regret this! I reread the blog and think there’s some worthwhile, even illuminating stuff about this influential scene at the heart of the AI industry, and how it works. So, I figure better late than never, and might as well publish now.

The event was called “The Curve” and it took place November 22-24th, 2024, so all commentary should be placed in the context of that timeline. I’ve given the thing a light edit, but mostly left it as I wrote it late last year, so some things will surely be dated. Finally, the requisite note that work like this is now made entirely possible by my subscribers, and especially those paid supporters who chip in $6 a month to make this writing (and editing!) happen. If you’re an avid reader, and you’re able, consider helping to keep the Blood flowing here. Alright, enough of that. Onwards.

A couple weeks ago, I traveled to Berkeley, CA, to attend the Curve, an invite-only “AI disagreements” conference, per its billing. The event was held at Lighthaven, a meeting place for rationalists and effective altruists (EAs), and, according to a report in the Guardian, allegedly purchased with the help of a seven-figure gift from Sam Bankman-Fried. As I stood in the lobby, waiting to check in, I eyed a stack of books on a table by the door, whose title read Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality. These are the 660,000-word, multi-volume works of fan fiction written by rationalist Eliezer Yudkowsky, who is famous for his assertion that tech companies are on the cusp of building an AI that will exterminate all human life on this planet.

The AI disagreements encountered at the Curve were largely over that very issue—when, exactly, not if, a super-powerful artificial intelligence was going to arise, and how quickly it would wipe out humanity when it did so. I’ve been to my share of AI conferences by now, and I attended this one because I thought it might be useful to hear this widely influential perspective articulated directly by those who believe it, and because there were top AI researchers and executives from leading companies like Anthropic in attendance, and I’d be able to speak with them one on one.

I told myself I’d go in with an open mind, do my best to check my priors at the door, right next to the Harry Potter fan fiction. I mingled with the EA philosophers and the AI researchers and doomers and tech executives. Told there would be accommodations onsite, I arrived to discover that, my having failed to make a reservation in advance, meant either sleeping in a pod or shared dorm-style bedding. Not quite sure I could handle the claustrophobia of a pod, I opted for the dorms.

I bunked next to a quiet AI developer who I barely saw the entire weekend and a serious but polite employee of the RAND corporation. The grounds were surprisingly expansive; there were couches and fire pits and winding walkways and decks, all full of people excitedly talking in low voices about artificial general intelligence (AGI) or super intelligence (ASI) and their waning hopes for alignment—that such powerful computer systems would act in concert with the interests of humanity.

I did learn a great deal, and there was much that was eye-opening. For one thing, I saw the extent to which some people really, truly, and deeply believe that the AI models like those being developed by OpenAI and Anthropic are just years away from destroying the human race. I had often wondered how much of this concern was performative, a useful narrative for generating meaning at work or spinning up hype about a commercial product—and there are clearly many operators in Silicon Valley, even attendees at this very conference, who are sharply aware of this particular utility, and able to harness it for that end. But there was ample evidence of true belief, even mania, that is not easily feigned. There was one session where people sat in a circle, mourning the coming loss of humanity, in which tears were shed.

The first panel I attended was headed up by Yudkowsky, perhaps the movements’ leading AI doomer, to use the popular shorthand, which some rationalists onsite seemed to embrace and others rejected. In a packed, standing-room only talk, the man outlined the coming AI apocalypse, and his proposed plan to stop it—basically, a unilateral treaty enforced by the US and China and other world powers to prevent any nation from developing more advanced AI than what is more or less currently commercially available. If nations were to violate this treaty, then military force could be used to destroy their data centers.

The conference talks were held under Chatham House Rule, so I won’t quote Yudkowsky directly, but suffice to say his viewpoint boils down to what he articulated in a TIME op-ed last year: “If somebody builds a too-powerful AI, under present conditions, I expect that every single member of the human species and all biological life on Earth dies shortly thereafter.” At one point in his talk, at the prompting of a question I had sent into the queue, the speaker asked everyone in the room to raise their hand to indicate whether or not they believed AI was on the brink of destroying humanity—about half the room believed on our current path, destruction was imminent.

This was no fluke. In the next three talks I attended, some variation of “well by then we’re already dead” or “then everyone dies” was uttered by at least one of the speakers. In one panel, a debate between a former OpenAI employee, Daniel Kokotajlo, and Sayash Kapoor, a computer scientist who’d written a book casting doubt on some of these claims, the audience, and the OpenAI employee, seemed outright incredulous that Kapoor did not think AGI posed an immediate threat to society. When the talk was over, the crowd flocked around Kokotajlo, to pepper him with questions, while just a few stragglers approached Kapoor.

I admittedly had a hard time with all this, and just a couple hours in, I began to feel pretty uncomfortable—not because I was concerned with what the rationalists were saying about AGI, but because my apparent inability to occupy the same plane of reality was so profound. In none of these talks did I hear any concrete mechanism described through which an AI might become capable of usurping power and enacting mass destruction, or a particularly plausible process through which a system might develop to “decide” to orchestrate mass destruction, or the ways it would navigate and/or commandeer the necessary physical hardware to wreak its carnage via a worldwide hodgepodge of different interfaces and coding languages of varying degrees of obsolescence and systems that already frequently break down while communicating with each other.

I saw a deep fear that large language models were improving quickly, that the improvements in natural language processing had been so rapid in the last few years that if the lines on the graphs held, we’d be in uncharted territory before long, and maybe already were. But much of the apocalyptic theorizing, as far as I could tell, was premised on AI systems learning how to emulate the work of an AI researcher, becoming more proficient in that field until it is automated entirely. Then these automated AI researchers continue automating that increasingly advanced work, until a threshold is crossed, at which point an AGI emerges. More and more automated systems, and more and more sophisticated prediction software, to me, do not guarantee the emergence of a sentient one. And the notion that this AGI will then be deadly appeared to come from a shared assumption that hyper-intelligent software programs will behave according to tenets of evolutionary psychology, conquering perceived threats to survive, or desirous of converting all materials around it (including humans) into something more useful to its ends. That also seems like a large and at best shaky assumption.

There was little credence or attention paid to recent reports that have shown the pace of progress in the frontier models has slowed—many I spoke to felt this was a momentary setback, or that those papers were simply overstated—and there seemed to be a widespread propensity for mapping assumptions that may serve in engineering or in the tech industry onto much broader social phenomena.

When extrapolating into the future, many AI safety researchers seemed comfortable making guesses about the historical rate of task replacement in the workplace begot by automation, or how quickly remote workers would be replaced by AI systems (another key road-to-AGI metric for the rationalists). One AI safety expert said, let’s just assume in the past that automation has replaced 30% of workplace tasks every generation, as if this were an unknowable thing, as if there were not data about historical automation that could be obtained with research, or as if that data could be so neatly quantified into such a catchy truism. I could not help but think that sociologists and labor historians would have had a coronary on the spot; fortunately, none seem to have been invited.

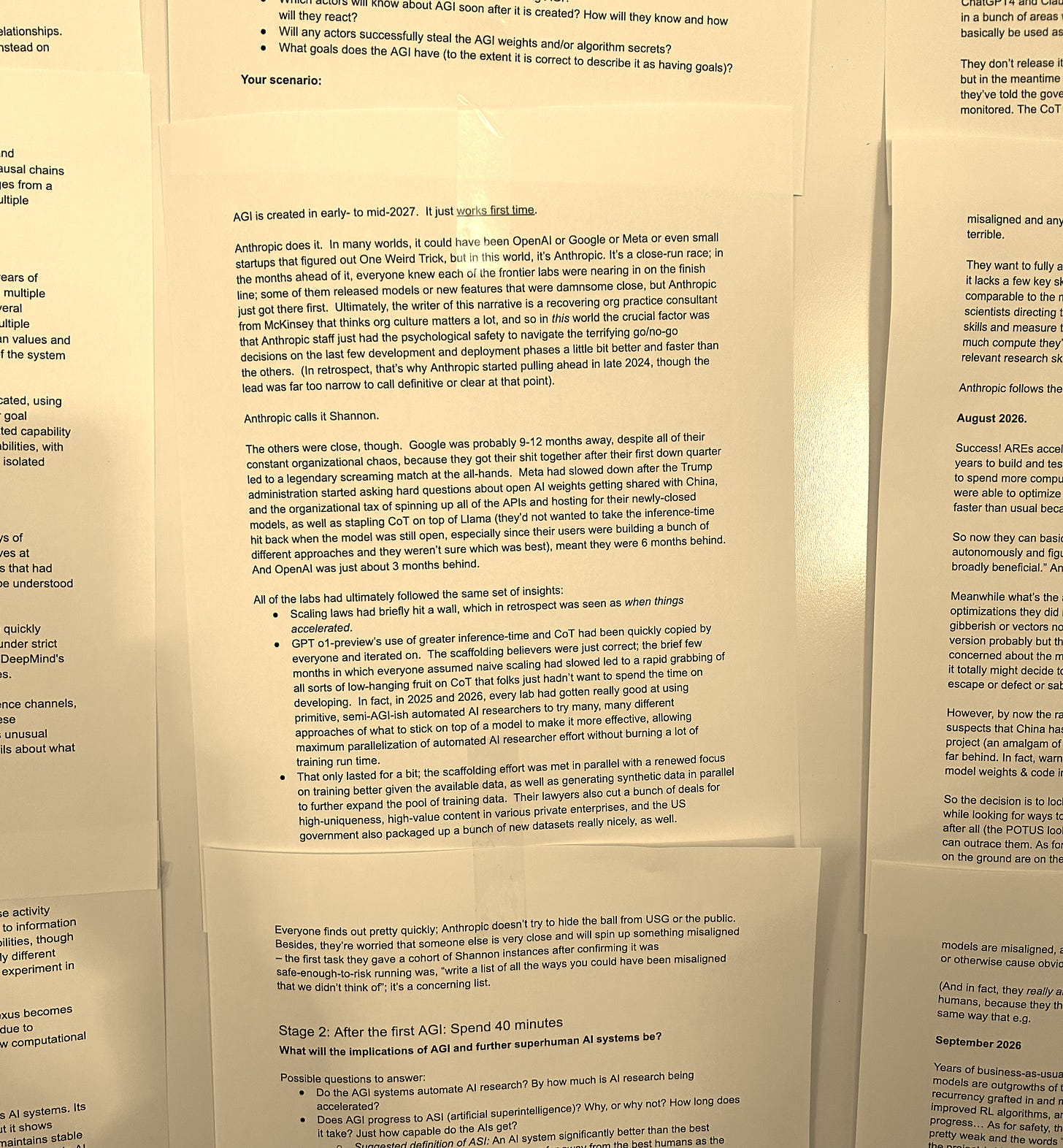

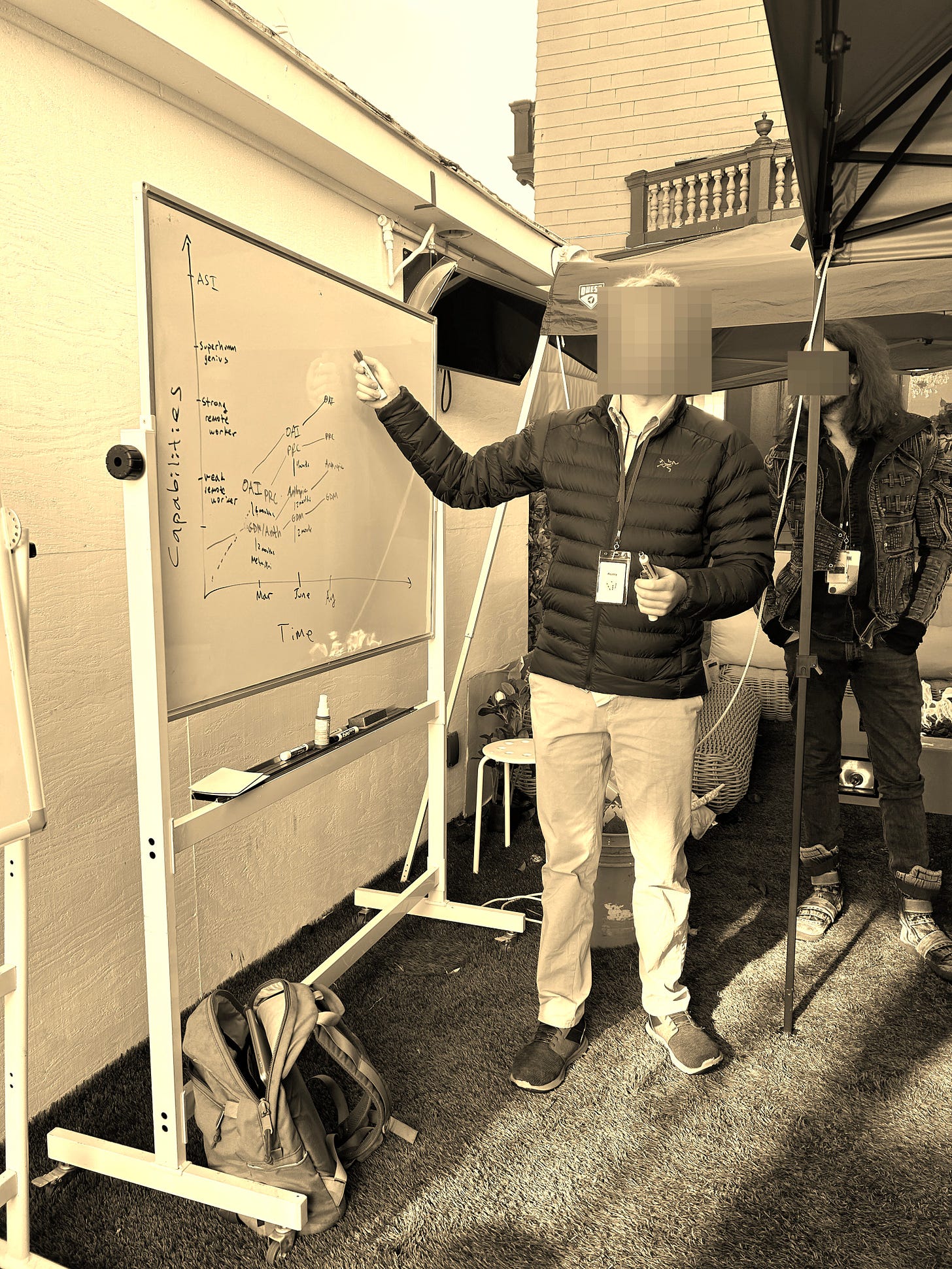

A lot of these conversations seemed to be animated displays of mutual bias confirmation, in other words, between folks who are surely quite good at computational mathematics, or understanding LLM training benchmarks, but who all share similar backgrounds and preoccupations, and who seem to spend more time examining AI output than how it’s translating into material reality. It often seemed like folks were excitedly participating in a dire, high-stakes game, trying to win it with the best-argued case for alignment, especially when they were quite literally excitedly participating in a game; Sunday morning was dedicated to a 3-hour tabletop role-playing game meant to realistically simulate the next few years of AI development, to help determine what the AI-dominated future of geopolitics held, and whether humanity would survive.

(In the game, which was played by 20 or so attendees divided into two teams, AGI is realized around 2027, the US government nationalizes OpenAI, Elon Musk is put in charge of the new organization, a sort of new Manhattan Project for AI, and competition heats up with China; fortunately, the AI was aligned properly, so in the end, humanity is not extinguished. Some of the players were almost disappointed. “We won on a technicality,” one said.)

The tech press was there, too—Platformer’s Casey Newton, myself, the New York Times’ Kevin Roose, and Vox’s Kelsey Piper, Garrison Lovely, and others. At one point, some of us were sitting on a couch surrounded by Anthropic guys, including co-founder Jack Clark. They were talking about why the public remained skeptical of AI, and someone suggested it was due to the fact that people felt burned by crypto and the metaverse, and just assumed AI was vaporware too. They discussed keeping journals to record what it was like working on AI right now, given the historical magnitude of the moment, and one of the Anthropic staff mentioned that the Manhattan Project physicists kept journals at Los Alamos, too.

It was pretty easy to see why so much of the national press coverage has been taken with the “doomer” camps like the one gathered at Lighthaven—it is an intensely dramatic story, intensely believed by many rich and intelligent people. Who doesn’t want to get the story of the scientists behind the next Manhattan Project—or be a scientist wrestling with the complicated ethics of the next world-shattering Manhattan Project-scale breakthrough? Or making that breakthrough?

Not possessing a degree in computer science, or having studied natural language processing for years myself, if even a third of my AI sources were so sure that an all-powerful AI is on the horizon, that would likely inform my coverage, too. No one is immune to biases; my partner is a professor of media studies, perhaps that leads me to skew more critical to the press, or to be overly pedantic in considering the role of biasses in overly long articles like this one. It’s even possible I am simply too cynical to see a real and present threat to humanity, though I don’t think that’s the case. Of course I wouldn’t.

So many of the AI safety folks I met were nice, earnest, and smart people, but I couldn’t shake the sense that the pervasive AI worry wasn’t adding up. As I walked the grounds, I’d hear snippets of animated chatter; “I don’t want to over-index on regulation” or “imagine 3x remote worker replacement” or “the day you get ASI you’re dead though.” But I heard little to no organizing. There was a panel with an AI policy worker who talked about how to lobby DC politicians to care about AI risk, and a screening of a documentary in progress about SB 1047, the AI safety bill that Gavin Newsom vetoed, but apart from that, there was little sense that anyone had much interest in, you know, fighting for humanity. And there were plenty of employees, senior researchers, even executives from OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google’s Deepmind right there in the building!

If you are seriously, legitimately concerned that an emergent technology is about to *exterminate humanity* within the next three years, wouldn’t you find yourself compelled to do more than argue with the converted about the particular elements of your end times scenario? Some folks were involved in pushing for SB 1047, but that stalled out; now what? Aren’t you starting an all-out effort to pressure those companies to shut down their operations ASAP? That all these folks are under the same roof for three days, and no one’s being confronted, or being made uncomfortable, or being protested—not even a little bit—is some of the best evidence I’ve seen that all the handwringing over AI Safety and x-risk really is just the sort of amped-up cosplaying its critics accuse it of being.

And that would be fine, if it wasn’t taking oxygen from other pressing issues with AI, like AI systems’ penchant for perpetuating discrimination and surveillance, degrading labor conditions, running roughshod over intellectual property, plagiarizing artists’ work, and so on. Some attendees openly weren’t interested in any of this. The politics in the space appeared to skew rightward, and some relished the way AI promises to break open new markets, free of regulations and constrictions. A former Uber executive, who admitted openly that what his last company did “was basically regulatory arbitrage” now says he plans on launching fully automated AI-run businesses, and doesn’t want to see any regulation at all.

Late Saturday night, I was talking with a policy director, a local freelance journalist, and a senior AI researcher for one of the big AI companies. I asked the AI developer if it bothered him that if everything said at the conference thus far was to be believed, his company was on the cusp of putting millions of people out of work. He said yeah, but what should we do about it? I mentioned an idea or two, and said, you know, his company doesn’t have to sell enterprise automation software. A lot of artists and writers were already seeing their wages fall right now. The researcher looked a little pained, and laughed bleakly. It was around that point that the journalist shared that he had made $12,000 that year. The AI researcher easily might have made 30 times that.

It echoed a conversation I had with Jack Clark, of Anthropic. It was a bit strange to see him here, in this context; years ago, he’d been a tech journalist, too, and we’d run in some of the same circles. We’d met for coffee some years ago, around when he’d left journalism to start a comms gig at OpenAI, where he’d do a stint before leaving to co-found Anthropic. At first I wonder if it’s awkward because I’m coming off my second mass layoff event in as many media jobs, and he’s now an executive of a $40 billion company, but then I recall that I’m a member of the press, and he probably just doesn’t want to talk to me.

He said that what AI is doing to labor might get government to finally spark a conversation about AI’s power, and to take it seriously. I wondered—wasn’t his company profiting from selling the automation services that was threatening labor in the first place? Anthropic does not, after all, have to partner with Amazon and sell task-automating software. Clark says that’s a good point, a good question, and they’re gathering data to better understand exactly how job automation is unfolding, and he hopes to be able to make it public. “I want to release some of that data, to spark a conversation,” he said.

I press him about the AGI business, too. Given he is a former journalist, I can’t help but wonder if on some level he doesn’t fully buy the imminent super-intelligence narrative either. But he doesn’t bite. I ask him if he thinks that AGI, as a construct, is useful in helping executives and managers absolve themselves and their companies of actions that might adversely effect people. “I don’t think they think about it,” Clark said, excusing himself.

The contradictions were overwhelming, and omnipresent. Yet relatively few people here were disagreeing. AGI was an inexorable force, to be debated, even wept over, as it risked destroying us all. I do not intend to demean these concerns, just question them, and what’s really going on here. It was all thrown into even sharper relief for me, when, just two weeks after the Curve, I attended a conference in DC on nuclear security, and listened to a former Commander of Stratcom discuss plainly how close we are to the brink of nuclear war, no AI required, at any given time. A phone call would do the trick.

I checked out of the Curve confident that there is no conspiracy afoot in Silicon Valley to convince everyone AI is apocalyptically powerful. I left with the sense that there are some smart people in AI—albeit often with apparently limited knowledge of real-world politics, sociology, or industrial history—who see systems improving, have genuine and deep concerns, and other people in AI who find that deep concern very useful for material purposes. Together, they have cultivated a unique and emotionally charged hyper-capitalist value system with its own singular texture, one that is deeply alienating to anyone who has trouble accepting certain premises. I don’t know if I have ever been more relieved to leave a conference.

The net result, it seems to me, is that the AGI/ASI story imbues the work of building automation software with elevated importance. Framing the rise of AGI as inexorable helps executives, investors, and researchers, even the doom-saying ones, to effectively minimize the qualms of workers and critics worried about more immediate implications of AI software.

You have to build a case, an AI executive said at a widely attended talk at the conference, comparing raising concerns over AGI to the way that the US built its case for the invasion of Iraq.

But that case was built on faulty evidence, an audience member objected.

It was a hell of a demo, though, the AI executive said.

Thanks for reading, and do subscribe for more reporting and writing on Silicon Valley, AI, labor, and our shared future. Oh, before I forget — Paris Marx and I hopped on This Machine Kills with Edward Ongweso Jr this week, and had a great chat about AI, China, and tech bubbles. Give it a listen here:

Until next time—hammers up.

Their "experiment" has become the world.

So for the British Empire as the Irish and Indians starved, the functionaries shrugged. What could they do? The market demanded no interventions... no mitigation of any kind.

And the "product" is remembered as "the bloody apron"...

These people are delusional. Like to totally detached from reality🥴