The original slop: How capitalism degraded art 400 years before AI

Why AI-generated Studio Ghibli memes are literally chintzy — and why you've probably got chintz all wrong.

Greetings all —

I’ve got something a little different today: The first original BITM guest post, from the great writer and editor Mike Pearl. Mike is a former VICE columnist, the author of The Day It Finally Happens, a frequent contributor to the New Republic, and a good friend. After the Studio Ghibli AI slopfest hit critical mass a couple weeks ago—it is, unfortunately, still ongoing—Mike sent me the following essay. Without spoiling anything, let’s just say it’s very, very Blood in the Machine, it’s great, and I think you’ll like it. Given that my experiment republishing Tim Maughan’s story Flyover Country feels like a success, I’m going to repeat the formula—the proceeds for all paid subscriptions triggered by this edition of the newsletter will be shared with Mike. Maybe this can be a way to support freelance writing on the site? Who knows! Thanks as always for reading, supporting, and sharing—hammers up, and enjoy.

Every time a generative AI image model gets released or updated, a similar cycle plays out: AI power users rush to test its capabilities, and highlight what they think are the most novel or meme-worthy examples. One of them goes viral, maybe more. Then, more and more people toy with the model and post the results online, and if I can, I test it out myself. Before long, whatever might have been compelling at first has eroded completely, and the effect of literally anything generated with the new software is that it just looks chintzy—by which I mean mechanical, cookie-cutter, and depressingly empty from an aesthetic standpoint.

For instance, it took approximately one week for the ChatGPT Ghibli meme to dissolve into chintz, and now certain images from actual Studio Ghibli movies make me wince, an effect I hope will be temporary, because nothing could be less chintzy than a painstakingly animated Studio Ghibli movie. But a piece of AI tech has come along and done its nasty work to the masters at Ghibli: zeroed in on something of surpassing beauty and turned it into chintz for fun and profit.

This feels like the only correct word. We use “chintzy” to describe something that has a deliberate aesthetic dimension—floral curtains, for instance—but which is obviously mechanized, causing it to seem cheap. Often something perceived as chintzy strikes a false note not because the consumer is a snob who knows better, but because the cheapness is so easily discerned it’s impossible for anyone not to notice.

Overwhelmingly on social media, chintzy AI images appear to be a statement. According to the writer Gareth Watkins, this is because the use of AI that I call “chintzy” and Watkins says “looks like shit” communicates group identity:

“No amount of normalisation and ‘validation’, however, can alter the fact that AI imagery looks like shit. But that, I want to argue, is its main draw to the right. If AI was capable of producing art that was formally competent, surprising, soulful, then they wouldn’t want it. They would be repelled by it. […] Why? Class solidarity. The capitalist class, as a whole, has made a massive bet on AI: $1 trillion dollars, according to Goldman Sachs.”

Capital has been here before with chintz—by which I mean real chintz, an artisanal craft from India. “Chintz” is originally a Hindi word, and if you're like most people, you’ve probably got the term all wrong. The type of pattern you associate with the world’s ugliest oven mitts and knockoff Lilly Pulitzer dresses is actually a sanded down, industrialized version of a visually rich handicraft that was first created about 400 years ago, in Hyderabad, India and flourished for at least decades before Europeans started importing it in high volume. I first encountered it in this context when my wife and I were in Jaipur, Rajasthan in 2019, and the rickshaw driver showing us around suggested we peek into a shop where handmade chintz is manufactured.

I took this video:

The simple patterns they were pumping out for the entertainment of sightseers were nice, but barely scratched the surface of what this craft can deliver. The original chintz makers used wood blocks, or even paintbrushes to dye vibrant images and patterns onto sheets of calico cotton fabric, many of which have held their vibrant color for hundreds of years.

This collection illustrates the range and depth of creativity in early chintz nicely. There was nothing chintzy about pre-European chintz.

And while it surprised me at first to learn that I had completely slept on what chintz actually was, the road from there to the adjective “chintzy” followed a very familiar course:

Humans make something beautiful.

It’s popular for a reason.

Capital profits from selling it, but…

Then capital wants to bypass the original creators to make more money.

Such efforts at reproduction are thwarted, which may make capitalists resent craftspeople.

Eventually capital can sort of reproduce the thing — well enough to remove human creativity from the picture anyway.

But what they really succeed in doing is creating crap.

The original is, at last, mistaken for crap.

Savvy readers of this newsletter will know that any time the British Empire pined for cheaper textiles, the world shuddered. But before anyone could really mass produce textiles with machines, the British East India Company, chartered, as we all know, in 1600, showed up in India with gold and silver, and returned to its cloudy little island spouting bits of Indian textile tech lingo like “khaki,” “calico,” “pyjamas,” “dungarees” and “chintz.” Much of the non-European world already imported Indian chintz before any Europeans got involved in the chintz trade. Other Europeans, notably the Portuguese, traded for chintz as well, but the British soon dominated trade in the region.

In her book Cloth that Changed the World: The Art and Fashion of Indian Chintz, the editor Sarah Fee presents 17 essays by different authors exploring the history of the trade. In the 1600s the European rich and poor alike loved and wore imported chintz. So, merchants started delivering larger and larger shipments—sometimes in place of goods like spices that they originally traveled to India to find—and flooded the market with popular and relatively inexpensive textiles, especially the brightly colored chintz cloth that could be made into exciting new dresses, waistcoats, and linings for straw hats.

European textile workers were getting squeezed, so they held “public burnings of chintz in protest” of the importers, as Fee explained in an interview with the Royal Ontario Museum. Throughout roughly the first half of the 18th century chintz was banned across a wide swath of Europe, although, Fee said, the rich, “continued to decorate their homes with it and wear it.” Only the poor and middle class were actually subject to anti-chintz laws, which allowed the authorities to strip people of chintz in the street if they were caught wearing any.

There was knockoff chintz at the time, and it was legal, but draconian enforcement of the ban on real chintz was still feasible, according to Fee, because European textile workers trying to make chintz could only create what we might now call “slop.” British textile producers could sort of approximate the right fabric with blended linen and cotton, but those bright chintz colors refused to stick to linen. Plus, at the time, Europe had not been able to replicate the right dye colors anyway, so Euro-chintz was mostly brown and gray.

As Fee points out, “There is just something whimsical and quirky and individual in each handcrafted piece from India versus the more mechanical printed or copper plate printed fashions, so you feel life and warmth in them.”

What most people know today as chintz, then, is the result of hundreds of years of technology and capital flattening and mass producing a once-vibrant art form: European printed textiles, often in prim floral patterns, mostly designed and manufactured during and after the Industrial Revolution. When you buy a vintage chintz tea cozy on Etsy, we accept that it’s “chintz” because textile capitalists appropriated, mass produced, and dominated the style, and the so-called chintz has largely replaced the original in our collective understanding. But it’s not true chintz any more than your pajamas today are true “pai jama” from the Indian subcontinent.

In 1851, George Eliot coined the adjective “chintzy”—adding a y—to disparage some ugly fabric, and the term has had negative connotations ever since. Slop chintz has erased the art from our cultural memory almost completely. Occasionally, reproduction chintz comes back into fashion, but these re-adoptions are tinged with irony, and the goods are once again tossed in the trash not long after.

In a 1996 ad for IKEA in the UK, a chorus of women urges you to “chuck out your chintz,” referring to mass produced floral fabrics from the 60s-era revival of the chintz look. No actual chintz was harmed in the making of this commercial.

But this process of artistic erosion once took hundreds of years, and now, thanks to generative AI, we can watch it happen in a day.

It’s probably not the case that Studio Ghibli’s reputation has been permanently or materially damaged by the proliferation of AI memes incorporating a soulless digital approximation of its aesthetic. However, I have now cringed at seeing the occasional frame from one of Ghibli’s less inspired still frames after being subjected to the memes more than I would have in the pre-meme times. The repetitive blandness of the AI images clues me into some of animation maestro Hiyao Miyazaki’s own tics more than I once would have. I can see, in other words, the imperfections in real Ghibli that highlight how bad fully-automated Ghibli would be.

If you don’t believe that the human act of creating is an essential part of art, or that art is more like a social activity—something communicated by the artist and received by the audience—than just a commodity to be consumed, then all this might not bother you. (And if you feel the urge to tell Hiyao Miyazaki to learn to code, your mind is alien to me). If that’s your mentality, a machine can certainly make art, and for that matter so can waves accidentally arranging pebbles on a beach. And perfectly acceptable art can undoubtedly be mass produced without any pesky “artist” being involved, assuming one has the material resources.

As Watkins puts it:

AI art, as practiced by the right, says that there are no rules but the naked exercise of power by an in-group over an out-group. It says that the only way to enjoy art is in knowing that it is hurting somebody. That hurt can be direct, targeted at a particular group (like Britain First’s AI propaganda), or it can be directed at art itself, and by extension, anybody who thinks that art can have any kind of value.

AI slop is, in some ways, a self-solving problem. We all learn to pretty easily distinguish lazy AI outputs from real or handmade work. Whatever new kind of AI artwork is being prompted into existence is the rapidly degrading chintz of the moment.

But ominously, chintz is just one art form, whereas slop is an all-consuming amoeba. It can find a new “chintz” every day, or multiple times a day if the gods of meme virality are feeling sufficiently vengeful. So let’s hope every time capital tries to do to something like Studio Ghibli movies what it did to chintz, it doesn’t leave a lasting cultural scar. And whatever you think of AI images, they do seem to be getting worse. Like chintz, the attributes that make them even remotely interesting are being sanded away over time. One of the attributes that makes something easily identifiable — and mockable — slop is homogeneity.

For example, in 2023, there were a few months in which a badly nerfed version of OpenAI’s Dall-E was available through Micosoft Bing as something called “Designer” (now it’s Bing Image Creator). By writing your prompt in nonstandard Unicode characters you could completely bypass the safety controls and generate all sorts of hideous, sometimes NSFW things. People used it to make surreal, but fairly convincing, fake Simpsons screenshots that looked like they were from the show’s 90s golden age (I don’t even think this required the Unicode cheat). This capability was quickly stripped out of Designer—most likely for the most obvious reason: copyright.

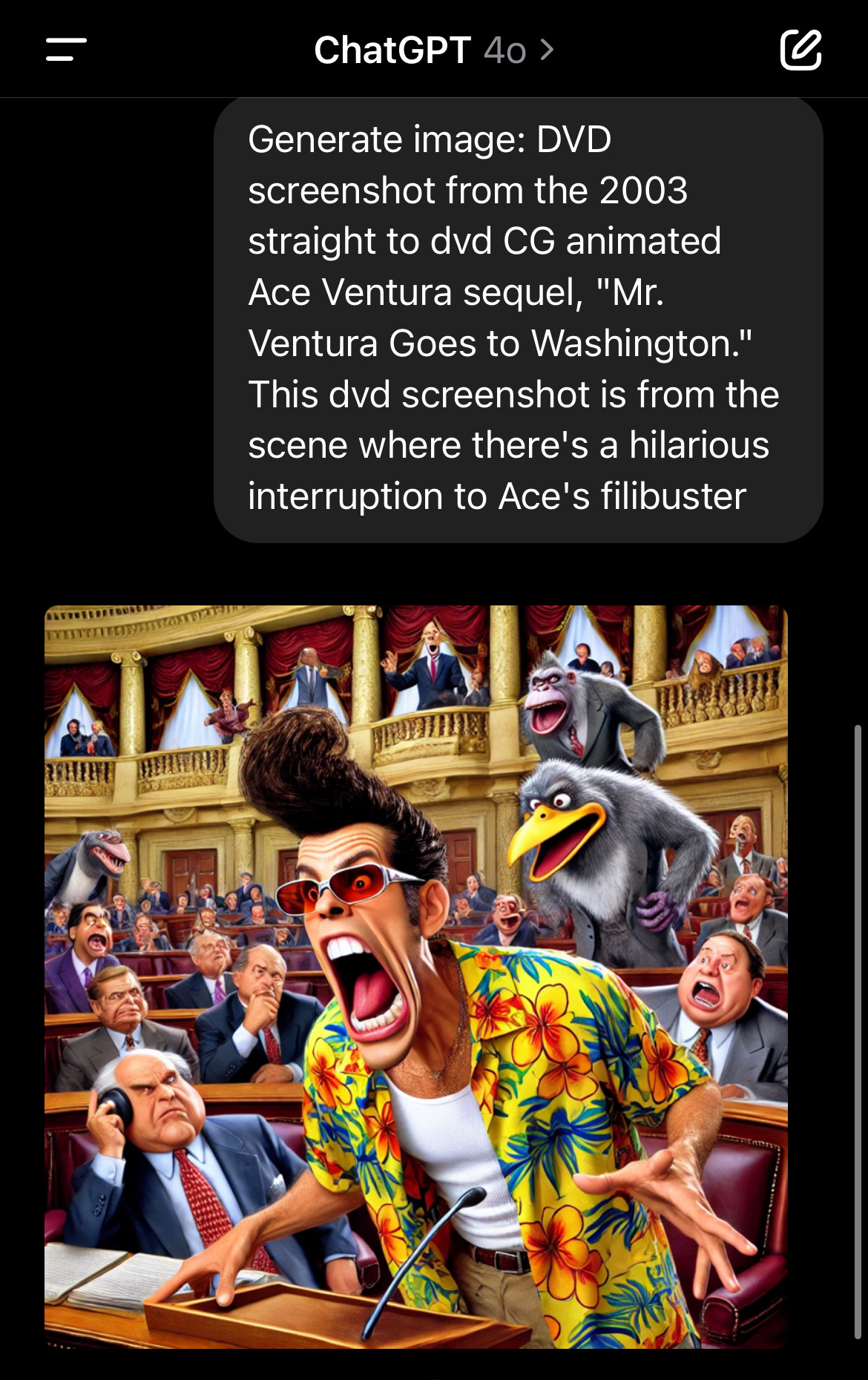

But you could make this Microsoft version of Dall-E do some striking things. For instance, here’s what happened in 2023 when I told Dall-E to show me what it would have looked like if they’d made a shoddy, straight-to-DVD computer-animated Ace Ventura sequel called Mr. Ventura Goes to Washington in 2003:

This is not art, but it’s also not unremarkable. The model created an animated version of the protagonist that looks like what that character would have looked like in a shoddy animated adaptation, and gave him a suit with a flamboyant tie, invented a villain seemingly inspired by character actor Kevin McCarthy, and captured what hands looked like in a Y2K era CGI kids’ movie really well. The image also looks somewhat convincingly like a screenshot from a movie. In the right circumstances you could glean some (not much but some) critical insight about the human-made work the model that made this image was trained on.

Now, two years later, OpenAI’s latest image model — the one that makes the Ghibli memes — produces this sort of thing for the same prompt:

This is in some ways a more arresting image — the subject is brighter, clearer, crisper, more contrast-y, and centered in the frame. His face also has more going on. As a bonus, there are wacky animals! Your lizard brain might be tempted to say this is the “better” image. But it’s profoundly worse in all the ways that matter: it doesn’t look like 2003, and it doesn’t look convincingly like a screenshot from a movie. It’s as if it just wants more people to like it, but it doesn’t make you feel like you’re in contact with something powerful and uncanny. When you see this, the main thing it makes one think is “Yep, there’s some AI slop.”

When mass production needs large quantities of images, geared toward the widest possible audience, exclusively with the aim of maximizing profit, over time everything remotely interesting about them gets worn away. The sort of thing that gets called “chintz” now does genuinely look kinda bad most of the time because it looks like what it is: a cheap floral pattern applied in a factory.

The qualities that made chintz seem “whimsical and quirky and individual,” as Fee put it, came from the fact that human beings applied the dyes by hand. Early AI images similarly had some lingering bugs and weirdness—artifacts of the authentic organic weirdness we all crave from art, or at least handicrafts, and will miss when they’re gone.

There’s “whimsical and quirky and individual” artwork all around you that’s not transcendently beautiful, but is, at the very least, human—from that card on a diner table telling you about a new milkshake flavor, to that lawyer billboard, to that banner on your local elementary school fence advertising a bake sale. I can only imagine how much uglier the world will look if AI does to all those in a handful of years what capital took four centuries to do to the original chintz. And I really hope that’s not where we’re headed.

The chintz in that video might be simple, but it still blew me away!

Another great piece.